Officials are now considering months of debate and testimony from New Yorkers and others who are concerned about the direction of the next 10 years of waste policy.

The public comment period on the draft state solid waste management plan closed Friday.

The state Department of Environmental Conservation said the plan “builds upon sustained efforts to reduce waste and advance the state's transition to a circular economy,” in an effort “to protect communities and mitigate the effects of climate change.”

“We certainly work to protect public health and the environment with our regulations and our decisions. And we are always striving to promote public participation, fairness and environmental justice," David Vitale, the agency’s division director for materials management, said during an April informational meeting.

But reaction has been mixed among the many contributors who have been closely following this process, particularly to the closure of the comment period.

“I don't understand why when a community that is impacted by waste infrastructure is telling you that they need more time that you just can't give them the time that they need and have requested,” said Monique Fitzgerald, a climate justice organizer on Long Island.

The draft state proposal was released in March, with a 60-day public comment period. Officials extended the outreach period twice until the end of day on Thursday, June 29 at the request of New Yorkers who have an interest in guiding the state’s environmental goals and expectations of local governments.

For industry leaders, the plan could give a boost to their waste transfer and disposal projects, building market incentives for local governments to adopt. State funding could also be steered to New York counties — and towns on Long Island — that are in charge of local waste management, planning to find new ways to reduce, reuse and recycle trash that ends up in landfills, incinerators and transportation to other states.

“It's a shift away from the linear ‘take-make-toss’ model, and more toward this circular economy that has so many ripple effects,” Vitale said in April. “So the circular economy designs out waste and pollution. That's the goal to keep products and materials in use as much as possible and regenerate natural systems.”

For Fitzgerald, this proposal could give her hometown the support it needs to shutter the Brookhaven Landfill and curb plans to build additional waste infrastructure near North Bellport and in other communities of color.

So far, she said the state ending the public comment period now has put the Brookhaven Landfill Action and Remediation Group (BLARG), which has been fighting for the site’s closure and cleanup since 2020, at a disadvantage to businesses that have more money and resources at their disposal.

“Because we have to organize, to ask for more time, and waste time on that process, instead of actually digging deep into what the waste plan says and actually come up with the analysis to respond and put forward some kind of action plan that the state can follow up on,” said Fitzgerald, co-founder of BLARG. “But instead, we’re stuck wrangling up people to say we need more time.”

“It doesn't make any sense — and that, in and of itself, is a travesty,” she added.

How money talks

The next stage of plan implementation may set the stage for how industry players and community groups fare in their efforts to influence state policy.

Will Flower, senior vice president of Winters Bros. waste disposal, said he believes his company has the most environmentally friendly solution for Long Island. Under its plans, waste would be transferred off the island by rail, a move which the draft state proposal could seek to limit if the trash is headed out of state.

“I’m gonna get my trash geekness on, but that’s the world I live in,” Flower said. “I’m going to talk about my world, which starts at the end of a driveway when people throw their garbage out. It’s not glamorous, but it’s critically important.”

The proposed Winters Bros. rail terminal, warehouse and recycling facility would be built on a 228-acre plot of land in Yaphank near the landfill. Thirty percent of the plot will be conserved as “green space.” The rest of the property would store, sort and ship more than 6,000 tons of construction and demolition debris per day from two mega-warehouses.

“We could get even more trucks off of the street, which would result in less air pollution and greater efficiency,” Flower said. “For every one rail car that you use, you can take five trucks off of the roadway.”

The Town of Brookhaven has determined that the proposed warehouses will have no negative impact on the surrounding areas and environment, an initial step towards approving development. Work on the site was expected to be completed in 2023, but has yet to begin. The NAACP, in opposition, has sued to make the town reexamine the impact.

If the facility goes ahead, over one million tons of Long Island trash will be delivered by truck to the Yaphank site annually. From there, it will likely be transferred by rail to landfills upstate and in Virginia, Pennsylvania and Ohio.

In addition to taking all kinds of debris, the Brookhaven Landfill accepts approximately 350,000 tons of ash per year created from three waste-to-energy facilities on Long Island, run by Covanta. The company’s plants incinerate garbage, turning it into energy, and creating ash as a by-product that needs to be deposited somewhere; that “somewhere” is the landfill.

This Yaphank site is one of four waste transfer stations in different stages of approval and development to offset the eventual closure of the Brookhaven Landfill, which is expected to stop accepting construction debris by the end of 2024 and reach capacity with ash deposits a few years later.

The Winters Bros. rail system does not include a disposal plan for the ash at this time, and Covanta is still working on its plans. “We’ve made no commitments or contracts at this time,” Dawn Harmon, the area asset manager for Covanta, said. “We’re still sort of just exploring all of our options and haven’t made a final decision about how we’re going to approach disposal after [the landfill] closes.”

Carlson Corp. also submitted a permit to the federal Surface Transportation Board and are waiting on approval to build a rail terminal in Kings Park.

“Environmental equality, [regulatory] determinations, and environmental impact statements take a long time, and rightly so. So, you know, we would be three [or] four years out,” Toby Carlson, president of Carlson Corp., said about the project.

The Townline Rail Terminal, if approved, will be built in a largely industrial area of Kings Park, which abuts a few neighborhoods. The proposed plan is to only ship out the garbage of the nearby areas of Huntington and Smithtown.

Carlson said he believes rail transportation is the most available short-term solution for Long Island’s waste problem.

“We have no choice but to either recycle [garbage], reuse it, stop consuming it or ship it out,” Carlson said. “Rail more than any other methodology of shipment is the most environmentally sensible way to transport large quantities of material off Long Island.”

The project is still in its early stages due to the lengthy approval process, but the surrounding community has made it clear that it does not support a new rail terminal in their area.

Bob Semprini, the president of the Commack Community Association, said community members are concerned about air pollution and excessive noise from the railway, but they are most concerned with their health.

“Most people are more worried about the ash because the ash is extremely toxic,” Semprini said.

A whistleblower complaint against Covanta filed by a former employee in 2013 has amplified fears of the ash being potentially toxic. A New York judge is considering the case, which accuses Covanta of dumping hazardous ash created by garbage from multiple Long Island towns at the Brookhaven Landfill. It alleges the ash is not treated to remove harmful chemicals and products, threatening people’s health.

Despite concerns, Harmon asserts the ash produced from their waste-to-energy process is non-toxic. “The bottom line is that no ash from Covanta’s facilities has ever been determined to be a hazardous waste,” she said.

Nonetheless, there are already operating rail terminals on Long Island, and some others are in the works, like the Winters Brothers’ proposal. Semprini said he feels that with the other railways in existence, the Townline Rail Terminal is unnecessary.

“There’s no reason to have this. This is strictly a business deal and that’s it,” Semprini said.

Learning from history

“Elected officials are pretty much just allowing industry to move what we do here, and that is the most anti-justice model,” said Monique Fitzgerald with BLARG, a group that grew after the murder of George Floyd and protests “to protect Black lives of the people in North Bellport” as it struggles to “close down, clean up and stop the transfer of waste to another community.”

Fitzgerald contends that the state plan doesn’t take account of the long and checkered history of how communities of color are impacted by waste infrastructure. And she recognizes that Brookhaven is not the first town to experience these problems.

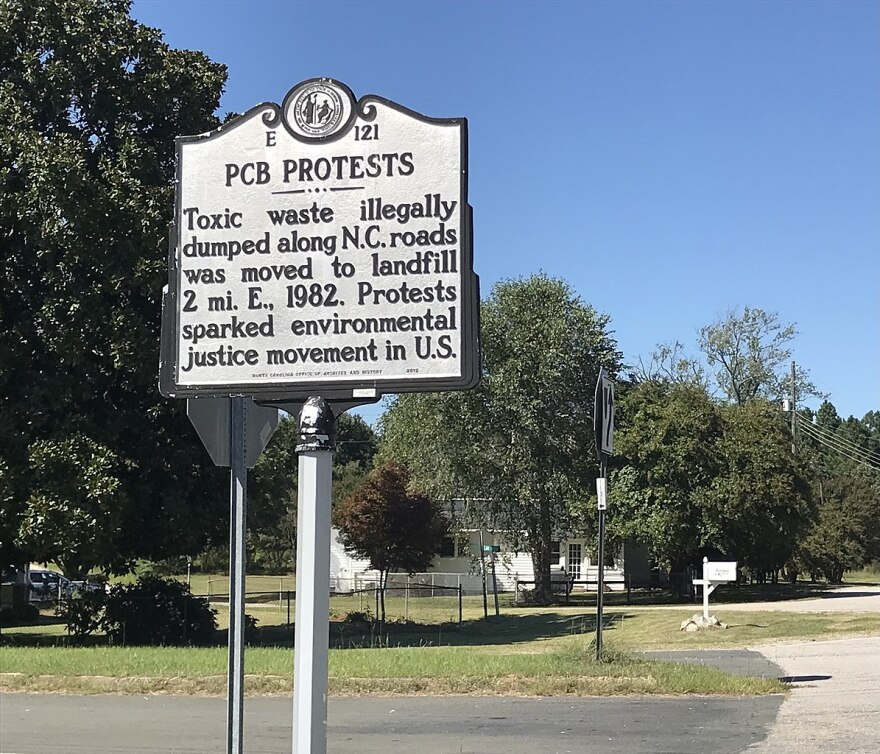

In 1982, residents of Warren County, North Carolina, a predominantly African-American community, joined together to oppose a landfill contaminated with polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) near their homes. Their protest, arguably, gave birth to the environmental justice movement.

After lawsuits and public hearings were not enough to prevent the Warren County landfill from opening, over 130 people marched two miles from Coley Springs Baptist Church to the site. There were 55 arrests on the first day, but they continued their fight for six straight weeks.

This led to a ground-breaking 1987 report by the United Church of Christ, “Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States”, which perhaps coined the phrase “environmental racism.” It found “race to be the most potent variable in predicting where these facilities were located—more powerful than household income, the value of homes and the estimated amount of hazardous waste generated by industry.”

The report set out a framework designed to protect workers, communities and the environment that remains relevant to the pollution allegedly affecting the Frank P. Long Intermediate School in North Bellport and surrounding area, which is the subject of nearly 30 lawsuits.

“The environmental justice framework rests on the Precautionary Principle for protecting workers, communities and ecosystems,” the report stated. “The Precautionary Principle asks, ‘How little harm is possible’ rather than ‘How much harm is allowable?’”

Among the recommendations were to involve communities of color in the transparent review and approval process of waste infrastructure.

“So that is why we're having this issue. We don't have that engagement with the people,” Fitzgerald said of the consultation process on the draft state plan. “How many times and how many ways do we have to say the same thing, right? We don't change our stuff. We don't change what we need.”

“They come up with all these ideas that, you know, they're going to change the world with. But literally, they're only in it for their pocketbook, and their money — and everyone without money to be damned,” she added.

Twenty years after the original report, a follow-up study was commissioned, “Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty,” which revealed “racial disparities in the distribution of hazardous wastes [were] greater than previously reported.” According to Robin Saha, a principal author of the 2007 report, people of color had been “left-behind” by a combination of “redlining” and “historic white flight" from the cities.

“These were places where industry found it easier and cheaper to set up waste facilities, because of the lack of strong political opposition that you might get in the suburbs or in wealthier areas,” she said

Saha said he was “surprised” the same patterns persist today. “In fact, they seem to have gotten a little worse,” he said. “I had expected that the environmental justice movement would have been pushing back on citing new facilities near Black, Indigenous and people of color communities.”

So, with the public comment period over, Fitzgerald said New York should expect to hear an earful from communities of color, who have historically been left out of consideration — but are burdened the most by waste infrastructure.

Contributing reporting by Harriet Jones and J.D. Allen.

WSHU’s Trash Talkin’ series is produced in collaboration with Stony Brook University’s School of Communication and Journalism.