Most people think of the bubonic plague as the disease that killed a third of Europe’s population back in the Middle Ages.

“The plague never really went away,” says David Randall, a reporter and author of the history book, "Black Death at the Golden Gate."

Randall describes how the plague killed more than 7 million people in Asia and the Pacific Islands in the late 1800s, when modern global shipping began.

“It was only a matter of time before it reached San Francisco.”

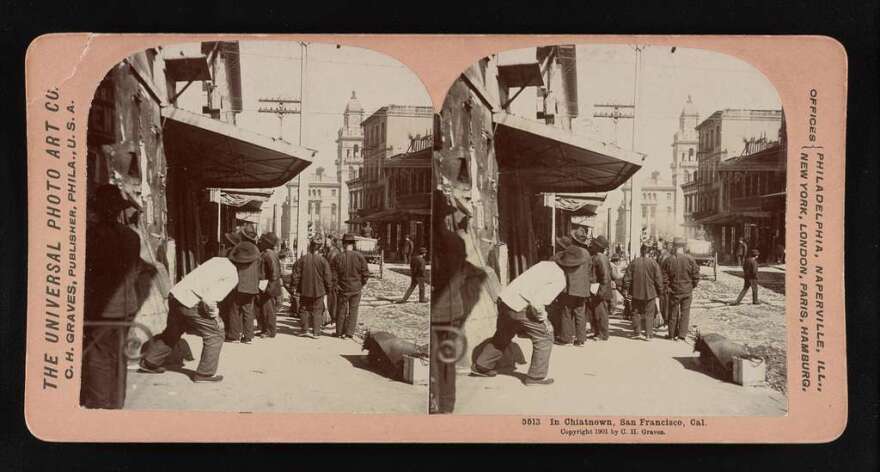

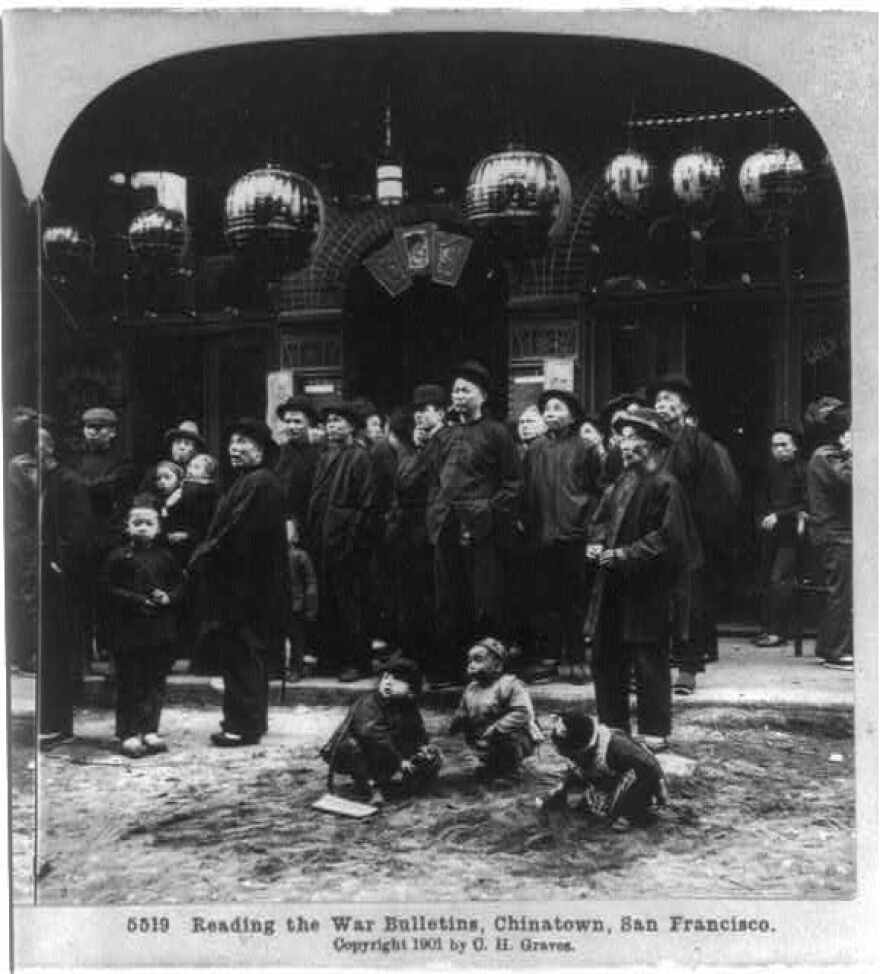

In March of 1900, a Chinese day laborer named Won Chut King was close to death. But roommates at his crowded boarding house in San Francisco couldn’t take him to a hospital. King went to a place called a “coffin shop” instead.

“In Chinatown at the time there was rampant anti-Asian bigotry,” Randall says. “It was very hard for the Chinese community, especially, to get things like death certificates, to access public health, access doctors. Coffin shops were really the last resort. People would take people...there and just wait for them to die.”

King passed away without comfort from friends or family. A coroner came to the coffin shop to issue a death certificate and examine King’s body.

“He notices a ‘bubo,’ which is a swollen lymph node on the groin or armpit. This is the bubonic plague, it’s how it gets its name,” Randall says. “He sees this and is terrified! He knows what it is. So, he calls for a quarantine right away.”

The quarantine only covered Chinatown. It lasted two days. No one believed public health officials that the plague had arrived.

“There’s a racial aspect to it as well,” Randall says. “People in Chinatown don’t want to admit that the plague is there because it seems to confirm all of the worst stereotypes about Asian immigrants: that they bring disease, that it’s a dirty place, that it’s unhygienic.”

There is a history of racist myths in the United States that diseases associated with Asia are especially dangerous. Sociologists say that’s one reason why politicians have used Asian communities as scapegoats for public health emergencies, but that same racism and xenophobia hinder disease prevention and treatment.

For example, in San Francisco, Randall says local politicians issued denials about the bubonic plague to comfort the white majority.

“It was literally considered an Asian disease that no other communities needed to worry about — and that is what made it so deadly in many ways.”

Plus, Randall says the public health director, Dr. Joseph Kinyoun, was scorned by his bosses. Kinyoun tried to develop a vaccine and quarantine the state, but the governor of California called him names in the newspapers.

“He started calling him ‘suspicious Kinyoun’ or ‘lying Kinyoun,’” Randall says.

Kenyoun was fired. His successor, Dr. Rupert Blue, started to look beyond Chinatown. He traced the plague to Italian and Portuguese communities, which were also near the city’s shipping port. The victims hadn’t been in contact with Chinese residents. Blue discovered the disease spread through fleas on rats, which roamed freely across neighborhoods.

“Doctors started coming up to Rupert Blue and saying ‘I’ve had white patients who had this disease and I was just calling it a form of pneumonia or I was calling it something else,’” Randall says. “This is the first time people say plague has been devastating the city for a long time — and no one ever wanted to admit it.”

Six years after Won Chut King died of the bubonic plague, San Francisco finally established a citywide public health response. It took the earthquake of 1906. Rats ran amok after the destruction. Officials had to get rid of them — and it meant cleaning the streets. This led to the creation of modern urban sanitation, like street sweeps and trash collection. Randall says he sees history repeating itself with the delay in fighting COVID-19.

“There’s denialism, there’s this idea that it’s outsiders who are bringing these diseases to us, as opposed to ‘what can we do to prevent disease?’” Randall says.

That fear of outsiders is xenophobia. Grace Kao is a sociologist at Yale University in New Haven. She says Asian Americans face xenophobia because no matter how many decades or generations their communities have been in the U.S., they are considered “forever foreigners.”

“It’s not really a new thing,” Kao says about anti-Asian sentiment during the pandemic, “It’s not as if the Asian Americans were just seen as regular people before this and suddenly they’re seen as foreign.”

Kao says today’s xenophobia is part of a centuries-long history of anti-Asian racism. Less than a hundred years ago, the U.S. government forced Japanese Americans into internment camps during World War II. Today, American politicians in both parties still talk about China like it’s the enemy. Kao says it's easy for the public to then blame the pandemic on anyone who may look Chinese. Now, data from a research advocacy group called Stop AAPI (Asian American and Pacific Islander) Hate show attackers who start anti-Asian hate incidents also invoked the president’s name.

Kao says media reports about Chinese markets selling bats make things worse: “They put people who look like me at real physical risk because people read those stories and they look up and there’s someone who’s Asian who is in the store and there’s feelings of ‘Oh my god, they’re carrying this disease! They’re not hygienic, they’re eating strange animals.”

Kao says she, thankfully, has not heard of any physical assaults where she lives in Connecticut, compared to California or New York. Still, there are incidents that are worrying.

Dr. Christine Won volunteers to work in the Medical Intensive Care Unit at Yale New Haven Hospital. On one of her days off, she took a hike with her two young daughters.

“There were quite a few people on the trail, but you know, people were responsible,” Won says. “We were all wearing our masks and we were trying to stay socially distant.”

Won says fellow hikers passed with a wave or a nod as they kept to a six-foot buffer zone. Then, Won saw a young couple walking her way with a little boy. They were not wearing masks.

“We saw them coming from a ways, so they were doing that whole kind of little dance with each group that they met. But when they came to us, they literally ran up the hill,” Won says. “They put their t-shirts over their face, which they weren’t doing with the other people before us. Then the young kid, the boy, was saying ‘Oh, they’re so disgusting!’”

The adults didn’t apologize. They went on their way.

“I actually had a flash of things I wanted to say, but I didn’t say,” Won says, “Like, you know, I looked at them and I say ‘My God, do you know that I take care of people that are not of my race everyday who have COVID virus? You know, I have not taken care of a single Asian person. I spend all day taking care of people like you, who are not wearing masks, who could very much be in my ICU tomorrow!’”

Instead of confronting those parents, Won had to discuss racism with her daughters. It’s the kind of discussion Asian American and Pacific Islander families have about racist incidents in school and in public. Advocates warn these discussions will become more common as people leave quarantine.

“Obviously it’s not the first time that I’ve been faced with racism, but what upset me most was that my children were there,” Won says she starts to get emotional talking about it. “When my 10-year-old daughter turns around, says to me, ‘Wait, why are they saying that to us? Are they saying that because we are Asian?’”

Won says it was a difficult conversation to have.

“Then my daughter says, ‘We’re not even Chinese!’ and I said, ‘I know, but it shouldn’t even matter!’”

They went along the trail. Won says her daughters seemed fine. She thought about it more than they did.

“I felt sad. Mostly, I felt more sorry for that young child, that 6-, 7-, 8-year-old boy,” Won says. “I thought, ‘My god, the adults are one thing,’ but I thought, ‘this is how they’re bringing up their child! That’s really scary!’”

Won says she thinks President Donald Trump talks about COVID-19 like it is some kind of Chinese conspiracy when he calls it “the Kung-Flu.” At a press conference during protests of the police killing of George Floyd, Trump said a strong economy is the greatest thing for race relations. Then he blamed the stalled economy on “the China Plague.”

This story is part of the WSHU series “Virus of Hate,” reporting on anti-Asian racism in the age of COVID-19. This series is supported by the Graustein Memorial Fund.