When Masjid Al-Baqi submitted its plan to expand its cramped one-story mosque facilities in 2018, they desired practical renovations to support the needs of their growing congregation.

But instead, they’d fight a seven-year multi-million dollar legal conflict against the affluent suburb of Oyster Bay, one in which the town they called home for the past 22 years would challenge their religious freedom through the use of zoning laws. The town and Masjid Al-Baqi reached a settlement in November of this year, finally granting the small but resilient mosque the opportunity to expand under scaled-back terms.

A WSHU investigation has found over 70 instances of anti-mosque development opposition across the country within the last 20 years, according to data compiled by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Pew Research Center and independent research.

These instances have arisen either from organized community opposition or administrative roadblocks in the approval process. Of these, more than 50 instances have occurred due to municipal authorities stonewalling mosques. The decades-long pattern has illuminated how zoning laws have been increasingly employed to discriminate against religious groups, but especially toward Muslim Americans.

On Long Island, the number of mosques has soared from two dozen a decade ago to roughly forty now. With Zohran Mamdani making history as the first Muslim American to lead New York City, the monumental impact of the event begs the question of how representation could shape acceptance of Muslims and Islam.

LEGAL OBSTACLES

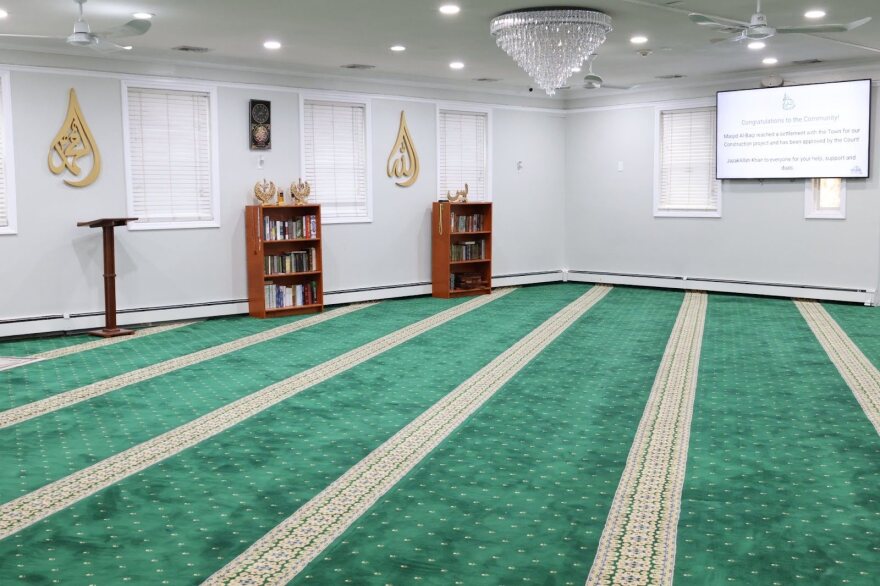

More washing areas and sinks to use for Wudu, an Islamic ritual done before prayer, designated classrooms to teach children about their faith and a room for congregants to celebrate Iftbar, a fast-breaking meal during Ramadan, were some of the spaces Masjid Al-Baqi hoped to provide with the expansion.

The Bethpage mosque, owned and operated by Muslims of Long Island (MOLI), an Islamic nonprofit organization, sought to tear down its separate two existing facilities and renovate it into a single three-story mosque.The mosque is located at an intersection between Stewart and Central avenues. Imran Makda has attended the mosque weekly since 2001. As a member of the mosque’s Board of Trustees and one of the two individual plaintiffs in the lawsuit, he expressed that the choice to pursue the case was one they felt was necessary.

“That decision wasn’t really made until we were officially told that the town [had] rejected our application right up until that time,” Makda said.

The mosque overcame several obstacles along the way. The first hurdle is the Town’s Department of Environment Resources’ (DER) years-long regulatory review. Minor mistakes including having to resubmit applications after using the wrong acronym, “TUB” instead of “TOB” delayed the application process. Despite the significant delays, Masjid Al-Baqi was ultimately found not to create new issues with parking.

During the process, the town issued a parking ordinance in 2022 that stonewalled the mosque from expanding. The law changed to require places of worship to have more parking spaces than before. Instead of mandating religious organizations to have one parking space per 100 sq. ft. of floor space, places of worship were now expected to have a minimum of 155. At that time, the mosque had only 86 parking spaces, a long way away from the recently required amount.

In November 2024, the town’s Planning Advisory Board (PAB) voted unanimously to deny Masjid Al-Baqi’s application, despite passing the DER and also gaining the approval of several members of the Nassau County Department of Public Works (DPW).

According to the complaint filed, the PAB’s denial of the mosque since 2018 was the only time the board had denied an application.

In January 2025, Masjid Al-Baqi filed a lawsuit against the town, claiming the obstacles blocking the mosque from expansion were due to religious discrimination. They sued on the basis of the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA), a federal law aimed at granting houses of worship land protection rights at the local government level.

Muhammad Faridi, an attorney of Linklaters LLP law firm representing the mosque, emphasized the impact the town’s zoning denials and delays had on the mosque.

“The Islamic community at Bethpage feels like outsiders that they're not welcome there,” he said. “These are folks who are committed to the town. They're committed to raising their families there. They love their neighbors. They love the town.”

According to a 2015 report by the Pew Research Center, Muslims composed roughly 1% of the U.S. population. In their 2020 report, the U.S. Department of Justice discovered that the religious group filed the most RLUIPA lawsuits and amicus filings, a finding that has “significantly exceeded” the Muslim population in the United States.

In August of this year, the town and Masjid Al-Baqi reached an agreement. According to Makda, congregants broke out in tears upon hearing the news. Although less than two weeks later, the town had abruptly backed out of the agreement.

“We were really utterly disappointed at that point in time,” Makda said.

Unusual challenges later on catapulted the lawsuit to the top of national headlines. The town’s usage of a testimony of an imaginary grandma and a self-described bigoted traffic expert who was found to have anti-Muslim remarks on his social media was reported by multiple media outlets and became an epicenter of controversy.

After two proposed settlements and one U.S. Department of Justice investigation into their case, the Bethpage mosque secured a long-sought-after $3.95 million settlement in November 2025.

“We never gave up hope,” Makda said. “You're not supposed to give up hope. You just keep fighting and you just keep doing the things that you think are right for yourself and your community.”

“I feel like it’s a better settlement than what we had before,” Moeen Qureshi, a member of MOLI’s construction committee and congregant of Masjid Al-Baqi since 2015.

Under the settlement, the mosque was allowed to create a single three-story mosque consisting of 9,950 sq. feet at ground level or above, down 1,150 fewer square feet than the original settlement. The mosque will also have a maximum occupancy of 295 people, instead of the originally proposed occupancy of 464 people. According to Makda, the mosque gained roughly 25 new parking spaces. The town issued a new traffic light and an enhanced parking lot and required the mosque to pay for a crossing guard over the course of 18 months. As part of the settlement, the town repealed the parking ordinance that they previously imposed on Masjid Al-Baqi.

In response to a request for comment, the spokesperson for the town of Oyster Bay responded with the town’s statement from the settlement agreement.

According to the written statement, Town Supervisor Joseph Saladino said, “This agreement resolves planning concerns and allows us to move forward as one community – with a smaller facility, less occupancy, improved traffic safety, added on-site parking and a shared commitment to safety, quality of life and mutual respect in Bethpage.”

COMMUNITY RESISTANCE

Faridi believed the town’s sudden withdrawal from the agreement was driven by opposition from its residents.

“What happened after the settlement was announced is that some of the residents who have very problematic and bigoted views towards Muslims, Islam and immigrants came out of the woodwork,” he added. “They began writing to the town leadership, sending emails [to] leadership on Facebook and other social media outlets,”he said.

On August 19, amid news of the settlement breaking out, a Change.org petition was created where over two thousand people signed, urging town leaders to vote no on the settlement.

A paragraph from the petition read, “Supervisor Joe Saladino and the Town of Oyster Bay Town Board are planning to hold an emergency meeting to approve a settlement to allow a monstrosity of a Mosque to be built in our community.”

The comment section included concerns from community members over potential traffic issues, but it also contained comments with Islamophobic remarks and slurs.

Makda said the petition did not dissuade their mission to expand.

“We are living in a different age of social media, and sometimes, these types of things sort of take a life of their own, and the negative commentary then takes hold….We don't know whether these are our neighbors or not. Maybe they are, maybe they're not,” he said.

“We actually brought the town officials in here, and they were shocked to see how we were operating,” he said about the mosque’s motivation to pursue a lawsuit. “I'm not saying it's our fault or their fault that communication never happened, or that physical communication never happened, but that's something we all could work on.”

“We sort of showed them and said, ‘Listen, of course, the town residents are concerned about the parking issue. Maybe there's an avenue for us if you're able to get access to that water basin, perhaps that would add another 25 [or] 30 parking spots.’ It sort of opened their eyes. And they said, ‘Yeah, this is definitely something that we can look into.’ They actually started making phone calls as soon as they left.”

Masjid Al-Baqi is not the only religious organization that has battled Oyster Bay on the basis of RLUIPA. In 2016, the Guru Gobind Singh Sikh Center filed a lawsuit against the town.

Daisy Khan, a staunch advocate for Muslim representation and women’s rights, said anti-Mosque sentiment often stemmed from bigotry. In 2010, Khan and her husband, Imam Feisal Adbul Rauf faced national controversy for their mosque project Cordoba House, which opened up two blocks away from the World Trade Center site of the September 11, 2001 attacks.

“The backlash to the project taught me that the resistance to Muslim institutions isn't really about that particular building. It's about not wanting to accept them as your neighbor or full citizen and ultimately it's about preventing Muslims from belonging,” she said.

Khan expressed how she believed anti-mosque opposition often stemmed from bias.

“I think that all of these zoning disputes are not isolated at all. It's actually part of a long-documented pattern when Muslim communities across America face barriers when they try to build or expand their houses of worship. From Tennessee to New Jersey to California, projects have been installed, denied and dragged [on],” she said.

Khan called them “the modern tools that are used to religious[y] discriminate. They are applied very selectively [and] inconsistently.”

A SECOND MOSQUE TAKES ITS ZONING FIGHT TO COURT

Less than 12 miles away from Masjid Al-Baqi, Hillside Islamic Center has also filed a lawsuit against the Town of North Hempstead for denying their proposal to expand their facilities. The proposal included adding a third story to their building and demolishing two other buildings for an additional parking lot.

In February of 2024, the New Hyde Park mosque sued the town on the basis of Article 78, a procedure that allows individuals and entities to challenge administrative decisions. In January 2025, the state Supreme Court sided with the Center, allowing it to expand and create an additional parking lot.

A spokesperson for the Town of North Hempstead and the town’s attorney did not respond to requests for comment.

In a Nassau County Planning Commission (NCPC)’s July 2024 meeting, Commissioner Reid Sakowich alluded to his experience living in New Hyde Park and seeing the Hillside Islamic Center, which informed his experience with Masjid Al-Baqi.

“I’ve lived this experience in New Hyde Park…. I’ve seen Hillside Avenue in New Hyde Park shut down on many, many, many times by people just being late for services and just leaving the cars out on the roads,” he said.

Despite improvements in Masjid Al-Baqi’s safety issues, Sakowich implied his opposition towards the expansion wouldn’t change, although the two are separate buildings.

“Their fix of the traffic flow, they’ve definitely increased it, but I live in New Hyde Park, and it’s just horrendous,” he said.

Abdul Aziz Bhuiyan, Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Center, said he felt the denial was rooted in bias against Muslim Americans.

“The expansion that we were looking for was all within our zoning. In other words, zoning allows us to expand the square feet that we're asking for. We didn't ask anything beyond that,” Bhuiyan said. "I mean, the community feels betrayed, that elected officials will be biased against the community.”

As of now, that fight is still ongoing.

MUSLIM REPRESENTATION

Next door in New York City, residents elected Zohran Mamdani as their first Muslim-American mayor.

New York is reported to have the largest population of Muslim Americans in the country, with over 700,000 residents living within the state.

Qureshi expressed the positive impact Mamdani's recent mayoral win had on new generations.

“It's breaking barriers for my kids to see that first Muslim American mayor for New York,” he said.

Qureshi described Mamdani as being an example of how Muslim Americans could follow different paths than those previously stereotyped.

“We're at this point where we need to start making a change. And if Mamdani is there, then tomorrow, my daughter or my son can say the same thing that I, you know, what I could earn for politics,” he said.

Musa al-Gharbi, a professor at Stony Brook University’s School of Communication and Journalism, said the politics of Long Island has played a part in shaping the outcome of anti-mosque development cases.

“It's that the political constitution of Long Island is a little bit more right of center compared to New York City, but it's also the case that demographically Long Island is different from New York City. It's changing, and it's changing in ways that sometimes some of the existing population are uncertain about or uncomfortable,” he said.

In a study by POLITICO, researchers found that Nassau County, where Masjid Al-Baqi and the Hillside Islamic Center are located, was one of the only areas across the state where a red wave emerged during this year’s November elections.

SHIFTING DEMOGRAPHICS

From 2010 to 2020, Long Island experienced a dramatic shift in its racial demographics. Research from Molloy University has found that Long Island has become more diverse, with the percentage of residents of Hispanic and Asian descent increasing significantly. From 2010 to 2020, the percentage of Asian residents jumped from 5% to 8%.

Khan explained that Mamdani’s win emphasized a positive shift towards representation and Muslim acceptance.

“It's very clear that it's part of the larger shift and how Muslim Americans are asserting their right at every level,” she said. “Their right to serve, their right to be in leadership, their right to their religious freedom, their right to speech. And they want to be visible, and he is proof that Muslims are stepping into leadership.”

For Makda, the stereotype of Muslims being “outsiders” doesn’t align with reality.

“When we pray, it's a different type of prayer. When we dress up, it's a different type of dress. But at the same time, we're normal human beings,” Makda said.

Qureshi described his hopes for the future of Muslim Americans and the societal ideals he hopes will change.

“There's a lot of political noise that happened in the background, especially over the last, I don't know, maybe 10,15 [or] 20 years,” he said. “It has become polarizing. But it's not polarizing when I'm talking to my neighbor, right? It's not polarizing when I'm talking to my co-workers that I've known for so many years. So when we establish relationships and bonds at a local level, at a personal level, it's a beautiful country, right? It's a beautiful place to live in.”