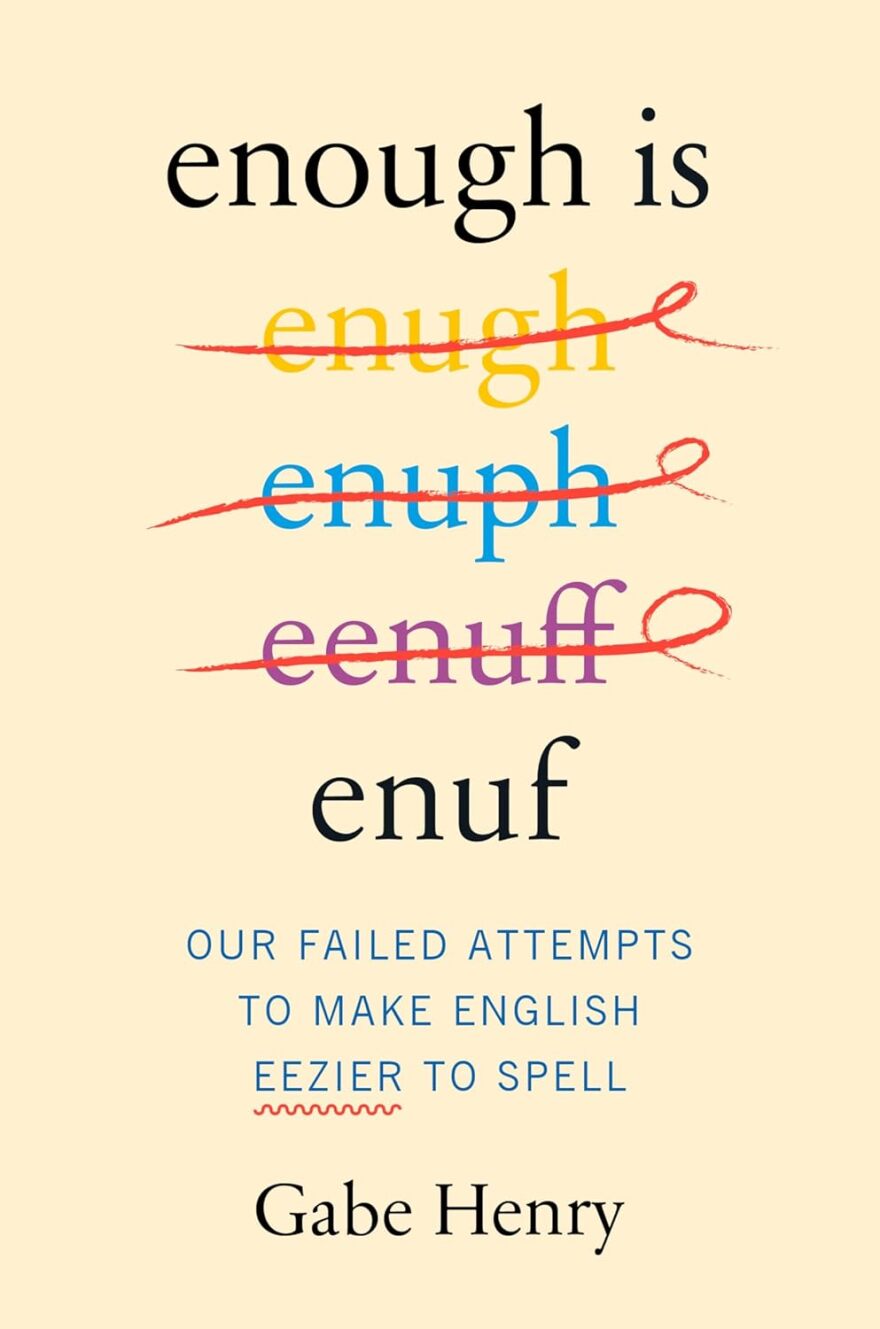

There are some among us who can’t tell time from an analog clock, especially one with Roman numerals, and think that “n-i-t-e” is the spelling of night, and that the pronoun “you” is fine if written as the letter U. They tend to be younger folks, or older folks who want to be younger. The ironic fact, though, as writer and humorist Gabe Henry shows in his informative and entertaining new book Enough is Enuph, Eenuff, Enuf:- each adjective spelled differently – spelling reform has always been around. Henry’s subtitle, Our Failed Attempts to Make English Eezier to Spell – “easier” spelled with two ees and a z – might suggest he’s against reform, but he’s sympathetic to the motives of reformers. The fact that American English has 44 sounds but only 26 letters created multiple duties for some consonants and vowels. But lasting change is hard.

The surprise, however, is how many accomplished enthusiasts argued for simplified spelling – for various reasons -- though most wavered in their commitment, depending on how fierce the opposition and how expensive it would be to implement phonetic reforms, especially in newspapers. Those enthusiasts included Benjamin Franklin, Charles Darwin, H.G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, Noah Webster, Andrew Carnegie, and President Teddy Roosevelt. In 1906, the Colonel, as TR liked to be called (speaking of spelling oddities), mandated federal employees use “thru,” for through, “tho” for though, and other shifts, but Congress voted it down.

Significantly, the simplified spelling movement was supported by abolitionists who saw it as a fast way to encourage literacy among former slaves. The movement also seemed pure and natural to vegetarians and patriots who wanted to cast off European elitism. And then there were women. Spelling reform attracted early feminists, reflected in Pitman Shorthand, which gave women prominence as stenographers when men went to war. Not for nothing was spelling reform associated with the suffragist movement and women’s rights.

Henry, whose previous work includes The Pun Also Rises, is especially enlightening on spelling bees, an obsession that took on racial as well as political significance, especially after a Black female student won a national competition. At times, as Henry’s research demonstrates, the simplified spelling movement fostered an advertising craze over Ks, as in Kleenex, Kool-Aid, Krispy Kreme. That was followed by toy marketers, such as ToyRUs, with its backward R and “Play-Doh,” spelled “doh.” Before that, mid-19th century evangelists pressed to replace letters with numbers -- the word “knowledge,” for example, would come out as 256. Don’t ask. But all along in our history, there was a sense among advocates that “spell as you wish” was related to educational freedom.”

Today, as Henry shows, between social media, and pop music, simplified spelling online is on the move because computers, unlike people, do not resist change. An underlying belief now is that simplified spelling represents bottom-up, from-the-people linguistic democracy. Still, opposition rules. Let’s close with an observation by Mark Twain, an on-again, off-again simplified spelling enthusiast, “It’s all right but, like chastity, you can carry it too far.”