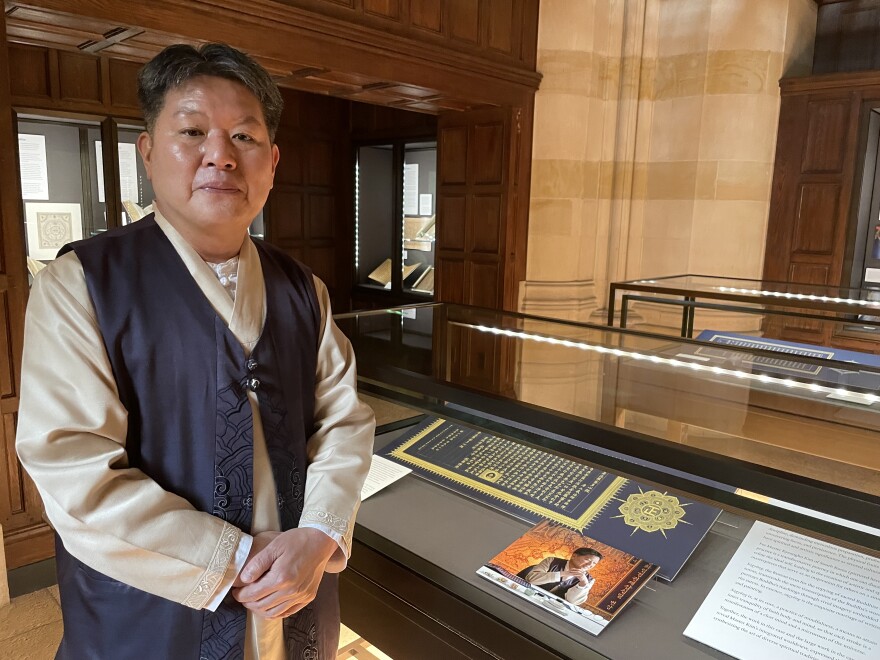

Kim Kyeong-Ho is an expert in sagyeong, the reproduction by hand of Buddhist sutras.

Master Kim sits at a drafting table — bright lights shining down on him — and dozens of people watching him. He’s in an event space in Yale University's Sterling Memorial Library.

He will copy characters onto a sheet of fine indigo-colored paper with a brush whose tip is just one-tenth of a millimeter. It’s delicate work. A translator narrates his commentary.

“When I touch it to the paper and accidentally take a breath, the 0.1-millimeter area can become a three-millimeter area," he said.

And that would ruin the entire page. Kim dips the brush in fine gold paint and a special kind of glue.

“And when we use this brush, we make sure that it is almost vertical to the surface.”

He slowly and methodically prints tiny golden characters on the paper. It takes about four minutes. He takes his time, he calls his practice an ‘aesthetic of slowness.’ The audience watches intently.

“So I've lost a lot of my touch during the ten days I didn't pick up a brush coming to Yale from South Korea," he said.

He shakes his head.

“What I wrote just now is considered a failure by my standards," he said. “But if you look at it like this, you can’t really tell where I messed up. But I know.”

These are also not the normal conditions for Master Kim. The studio is normally kept at nearly 100 degrees Fahrenheit to keep the glue from drying before he can apply it to the page.

“In my studio I don’t usually dress like this.”

He gestures at his shirt and mimes taking it off.

“I often take a 10-minute break every hour, and since I do this for over eight hours a day, in summers, I gotta take maybe three, four, or even six times to wash my face.”

Kim started this work as a young boy. He’s been doing it for more than 50 years. His specialty is sagyeong — the transcription of Buddhist verses called sutras. Sometimes they’re paired with extremely intricate illustrations. Jude Yang is a librarian for Korean Studies at Yale University.

“It has an old history, traditionally, through the Koreas," she said.

The university’s oldest Korean sagyeong goes back to the 14th century, and it’s written with the same gold ink and indigo paper Kim uses.

“The printing practice in Korea has a really long history," she said. "It's kind of extended of handwriting of sagyeong. We actually claim that one of these is older than the Gutenberg Bible.”

Kim’s work draws from Korean history, but also from religious traditions across the world. He’s inspired by the illuminated manuscripts Christian monks made in the Middle Ages and by Islamic calligraphy. Symbols inspired by other religions appear occasionally in his work, alongside the words of the Buddha.

“The basic tradition in both the East and West of transcribing the words of the saints — the mindset and the spirituality behind it is fundamentally the same," he said, speaking through a translator. "Everyone, all the scribes, did this as a form of spiritual practice. [T]he Bible and the Koran and sacred texts such as the Buddhist scriptures of the East, they all sort of come together in the same way.”

The exhibition is called Copying Sacred Texts — a Spiritual Practice. It runs through August 11 at the Sterling Memorial Library’s Hanke Gallery at Yale University.