The Brookhaven National Laboratory’s (BNL) Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider completed its last run last Friday after a quarter-century of data collection.

“We’re here celebrating the scientists, engineers, technicians and support staff who made 25 years of success possible, at Brookhaven, across the DOE labs, and with partners around the world,” BNL Associate Laboratory Director of Nuclear and Particle Physics Abhay Deshpande said before RHIC was shut down.

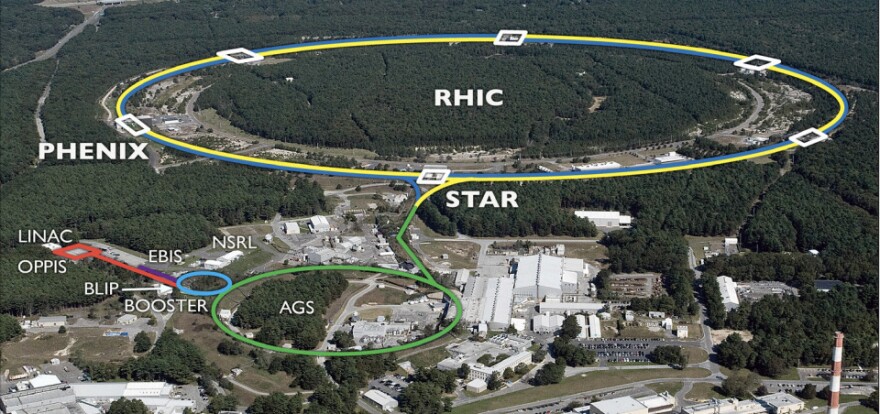

The Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) is a particle accelerator, meaning that small particles like protons spin around a loop fast, causing the particles to smash together. Scientists at Brookhaven National Laboratory are studying the way the protons in RHIC interact with each other, and more importantly, the fundamental forces that govern them.

Many were in attendance for the event, with members from Stony Brook University, the Department of Energy (DOE), and scientists at BNL coming together. A big red button (yes, exactly like the ones you see in the movies), was used to officially turn off RHIC. The button was pushed by the DOE Under Secretary for Science Darío Gil, which was followed by a round of applause from the surrounding crowd.

“What scientists discovered here surprised the world and transformed our understanding of the strongest force in nature,” Gil said.

RHIC made over 300 trillion collisions in total since 2000. RHIC’s data resulted in more than 650 scientific publications, and even though RHIC completed its last run, the data already gathered from RHIC will still take years, if not decades, to research. The 2.4-mile round collider collected information that remains prevalent for the advancement of science.

The final run of RHIC was less of a memorial and more of a celebration of a new beginning. RHIC will be revamped to turn into an electron-ion collider (EIC).

“The time of EIC has come now,” Deshpande said. “We just shut down a large, very, successful facility. And now we are looking forward to going to the next phase and using all of that knowledge and everything that we have built over the last 25 years and more into this future.”

Some elements of RHIC will remain the same. One of the loops in the collider belt will stay, while some others will be rebuilt. These parts of the collider are underground, forming a loop.

RHIC and EIC differ in what particles are colliding. In RHIC, heavy ions and sometimes protons are spinning around close to the speed of light. In EIC, electrons collide with protons or ions.

The applications of the research done with the EIC may seem distant, but BNL’s research will advance medicine, AI and national security, just to name a few.

Many scientists have started their careers with RHIC. More than 640 Ph.D. students received their degrees because of research done with RHIC. BNL does not expect this number to disappear with the EIC; they expect it to grow.

“One of my favorite parts about working at Brookhaven is getting to see my designs go all the way from concept through installation,” Jonathon Greene, a mechanical engineer at BNL, said.

BNL is one of 17 national laboratories, but its connections do not stop at the national level. Over 36 nations from around the world have contributed to science with RHIC, one prominent one being Japan.

“We are very proud of the strong trust we have built together,” Makoto Gonokami, president of RIKEN, which is a Designated National Research and Development Institute, said. “Our journey started in the early 1990s, and RHIC will always remain a symbol of trust and friendship between the United States and Japan.”

While BNL’s impact spans far and wide, a large connection is from Stony Brook University, roughly 20 miles apart. Honoring this relationship, Stony Brook University president Andrea Goldsmith was in attendance for the closing ceremony.

“It is so inspiring to be part of this momentous day where we're closing down RHIC, which has been a vehicle for advancing discovery and an incredible partnership between Stony Brook University and Brookhaven,” Goldsmith said. “[Stony Brook University is] looking forward to the next wave of discovery through the electron-ion collider and strengthening even more the partnership between Brookhaven and Stony Brook. Stony Brook is stronger because of that partnership and Brookhaven is stronger because of that partnership.”

Angelina Livigni is a reporter with The SBU Media Group, part of Stony Brook University’s School of Communication and Journalism’s Working Newsroom program for students and local media.