Columbus Day is here again — a few sales, a few parades and the post office is closed. Most people don’t get very excited. At least 13 states no longer celebrate Columbus Day at all, but instead have labeled the federal holiday as Indigenous People’s Day or Native American Day.

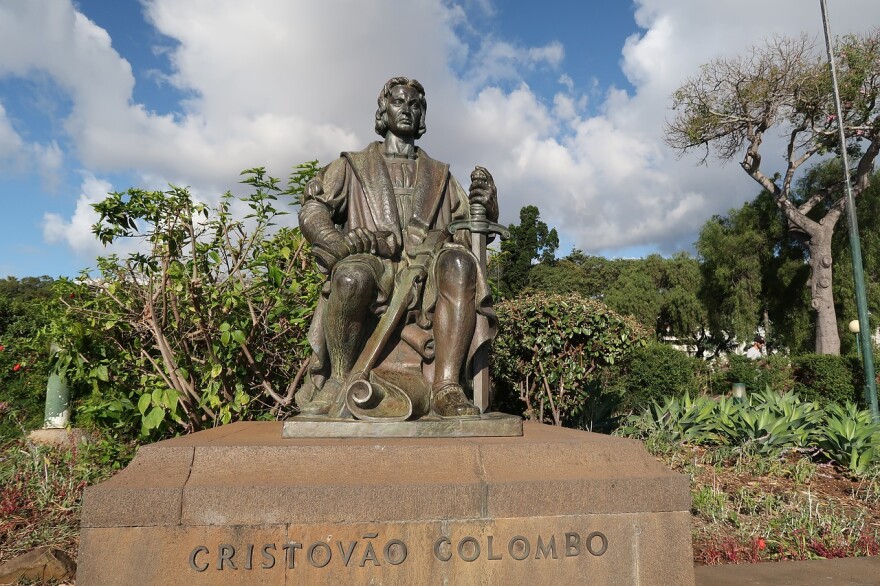

Christopher Columbus was never an ideal national hero. Brave he certainly was, but when he so boldly sailed the ocean blue in fourteen hundred and ninety-two Columbus, and his patron Queen Isabella, set a pattern of bad behavior for the whole Western world. In different ages this behavior has been called piracy, economic imperialism, prospecting, entrepreneurship, gambling and corporate capitalism. But the basic motivation has always been the same passion that urged Columbus to undertake his dangerous exploits. According to one of his biographers, Columbus was driven by a "Burning desire to acquire riches, power and fame."

One thing we know for sure about history is that it remembers the winners. Who knows or cares anything about the hundreds of adventurers who tried to make that voyage and failed? History also remembers the generals, not the troops. The ordinary seamen who suffered and often died in the service of Christopher’s ambition might just as well never existed. Those men were so scared of sailing into the unknown that Columbus kept two separate logs: one that charted the ship’s real progress and course and the other, intended to reassure the hands, that seemed to show that they were on a much shorter and safer voyage. In other words, they were not heroes, they were victims.

History turns into myth very quickly, and 500 years is a long time. Once a historical character has been thoroughly mythologized, as Columbus has been, there is almost no chance of getting back to the truth. Without his myth Columbus would vanish from the collective memory like the grin of the Cheshire cat. The frustrating thing about history is that we don’t know and can never know what really happened. A careful look at almost any historical "fact" that everybody knows to be true will reveal it to be a myth. The Declaration of Independence was not signed on the Fourth of July, and baseball was not invented in Cooperstown New York in 1839. It’s as if we live halfway in a dream of a history that never was, a kind of false collective memory — and memory is always political.

The first historian of the Americas, Bartolomé de Casas, wrote in 1542 that: “The discovery was, on the whole, a bad thing.” What Columbus brought to the New World was war, disease, despotism, racism, slavery and religious persecution — all the things that had made Europe such an interesting place for the previous thousand years. Even Columbus himself was not a winner in the end. He got little profit out of his dangerous voyages. He was appointed Governor General of his newly discovered islands. But he acted with such brutality that he was recalled by Queen Isabella and died in poverty and obscurity.

But he pointed the way westwards towards a new utopia. Columbus changed the world map and, metaphorically speaking, marked this continent like a treasure map with an X saying “This is where the money is.” In doing so, for better or worse, he launched one of the greatest continuing migrations in history.

Copyright: David Bouchier