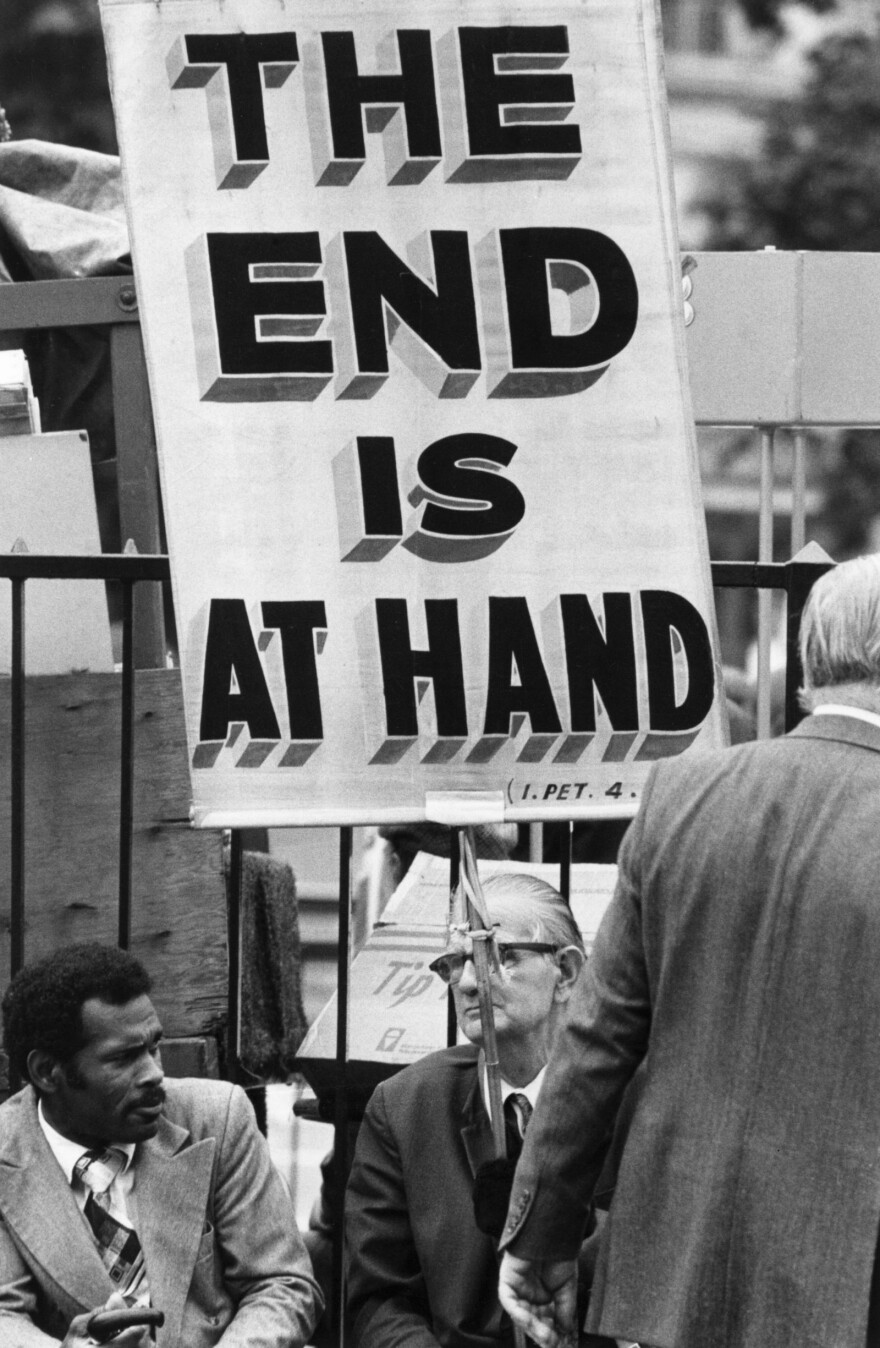

The end of the world has always been on my mind. One of my earliest memories is of the old men who used to parade around public spaces in the wreckage of London carrying placards announcing that the end of the world was at hand. I believed them and kept on believing them, because why would they do this if they didn’t know? But, my goodness, the end has been coming for a long time. We need and deserve a definite date for the apocalypse, and preferably a time of day, Eastern Standard Time, for preference. Then we can mark it on the calendar and make our plans accordingly. The future is much more manageable if it stops at a definite point. There’s so much less to plan and worry about.

For the last part of the twentieth century, the threat of the big bomb kept everyone on their toes. This was obviously the apocalypse that the old men were warning us about. We had a big scare in 1962 with the Cuban missile crisis, and by then, Hollywood had fallen in love with the apocalypse, so we had a string of movies—On the Beach, The Day After, Oppenheimer—just to remind us not to relax.

The old men with doomsday placards are no longer seen, not even in New York City, where they should be crowding the sidewalks. But they are still active, if you know where to look. They have retreated into the murky anonymity of the World Wide Web, where the dedicated catastrophist can find any number of doomsday prophecies: political tyranny, judgment day, economic collapse, nuclear annihilation, ecological calamity, domination by computers – so many choices, take your pick, you don’t have to choose just one.. Amazon is still selling survival kits. and the billionaires keep building their underground bunkers and stocking their private islands. It’s good to know that they will be OK.

We had a flurry of predictions about the end of the world before the year 2000 – remember the Y2K problem?. A Californian preacher promised the return of Christ and an apocalyptic earthquake for May 21, 2011. This failed to happen, and we had to wait a whole year for the next apocalypse, based on an ancient Mayan Long Calendar, the last page of which ended abruptly on December 21, 2012. Once again, nothing happened. The fascination with the end of the world is as old as history, and you don’t need to be much of a psychologist to figure out that it is simply the shadow cast by our own mortality.

If you, like me, prefer your bad news to be more up-to-date, there are a couple of half-hearted predictions for the immediate future. Some words of the ancient prophet Nostradamus suggest that 2025 will be our final year, although he doesn’t give a precise date – obviously not before today, or we would have noticed. A more recent prediction warns that an asteroid will destroy the Earth in 2026. But, in the realm of world-ending scenarios, deadly asteroids are two a penny.

The history of prophecy shows that the only way to achieve notoriety is to predict the worst. This also works well in politics. A happy prophet is a contradiction in terms. Nobody ever got onto the front page of the tabloids by forecasting that next week will be very much like this week, or that universal happiness and prosperity are just around the corner. We are, in short, a credulous and gloomy species, and we get the prophets and the prophecies that we deserve.