What literary text could seem further from reality these days than Beowulf — that approximately 1,500-year-old Anglo Saxon verse epic about a Scandinavian hero fighting monsters that’s known mainly by English majors and then, mostly in translation! Yet here are two new Beowulfs, different translations and genres, out this past August, that in their separate imaginative ways have something to say to our troubled times.

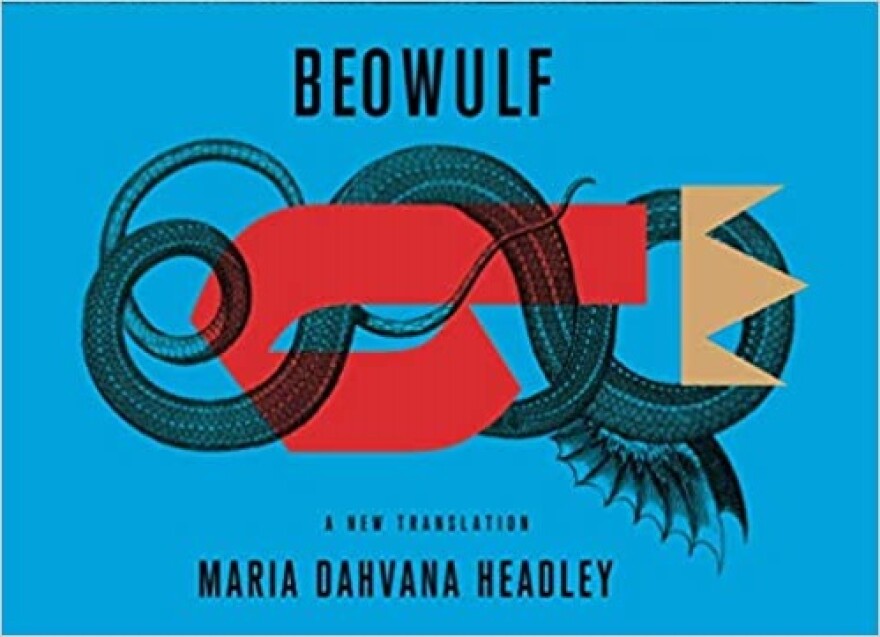

Maria Dahvana Headley, a NYC -based writer, did her own translation — rewriting is more like it. A radical feminist hip hop take that renders the opening Anglo-Saxon word “Hwaet” — which Nobel Laureate Seamus Heaney 20 years ago translated as “So” — as ... ready? ... “Bro.” Don’t freak out. The New Yorker says it works. But it’s East Hampton writer and artist Barry McCallion’s version that offers a unique take on the epic work. His is a beautiful, semi-abstract hand-painted book in colorful India inks and acrylic on semi-transparent parchment-like paper that faithfully reproduces and illustrates the last 672 lines of the poem.

Although Beowulf memorably bests the monster Grendel — with his hands only — and then vanquishes Grendel’s vengeful mother, McCallion focuses on the battle Beowulf undertakes 50 years later, when he’s an old man and his kingdom is threatened by a gold-hoarding dragon.

“Gold,” “hoard” — both solid Anglo-Saxon words, still with us. The poem says something about the eternal motives that spark wars and how war shapes culture and civilization. The Beowulf poet is looking back hundreds of years to a time of “dragon darkness” from the vantage point of an era of growing Christian influence, but he wonders, in effect, if the world will ever see Beowulf’s like again.

McCallion divides the last section of Beowulf into three parts: The Dragon Stirs, The Fight With the Dragon, and the Hero-King Interred. He also includes parchment pocket inserts before each section that contain Heaney’s rhythmic and alliterative translation. Then he presents the original text and his own art. Beige, cream, tan, grey tones rule, setting off the hero’s iridescent silver and gold-inked shield, sword and crown. Beowulf himself is sketched as a faceless helmet that resembles the Greek letter omega. Scenes are set against “stippled india ink backgrounds that create “a grainy, miasmal effect.” McCallion says that he associates with myth and antiquity. The dragon, by contrast, slithers in green and yellow, belching yellow-orange flames, until blood splotches mark the pages.

Significantly, the last illustration in McCallion’s book is of Beowulf’s funeral pyre, in earth tones. A mound of dirt, stones that look like dragon’s teeth. Though well on in years, Beowulf has fatefully sought out the fire-breathing dragon in his lair, though he intuits he will die. He knows though that he faithfully followed the code of honor and commitment to his people. He gave them wealth; he gave them peace. It is his sacrificial sense of what a ruler owes to those under his reign that distinguishes him among leaders, ancient and contemporary. Beowulf reflects, “I took what came / cared for and stood by things in my keeping,/ never fomented quarrels, never / swore to a lie. All this consoles me....” Perhaps it also consoled the Beowulf poet. Perhaps it may instruct us.