A distant relative recently contacted me about our family history. This is always disturbing, of course, because you never know what he might discover. What you already know may be bad enough. But the history my relative had revealed seemed to be relatively harmless, even boring, at least for the past two hundred years or so. In earlier centuries, the genealogical record soars into the realm of imagination, and our past was full of minor aristocrats, important landowners, and even an archbishop. The best thing about family history is that you can believe what you like.

Occasionally, I think about my ancestors, but not for long. I know almost nothing about them, and what I do know is uninspiring. My mother was born in 1909, and her mother, also a centenarian, was born in 1884. Before that, everything is lost in the smog of history. My father’s family seems to have appeared out of nowhere (probably from France) in the early 1800s, perhaps in flight from the Napoleonic tyranny, and distinguished themselves by their determined lack of distinction. They were all good, intelligent and hardworking people with one possible exception - my paternal grandfather, with the splendid name of Hubert, who ran away from the Army in 1892 and was not arrested until five years later. He was an all-around bad boy, a genuine original, an ancestor to be proud of.

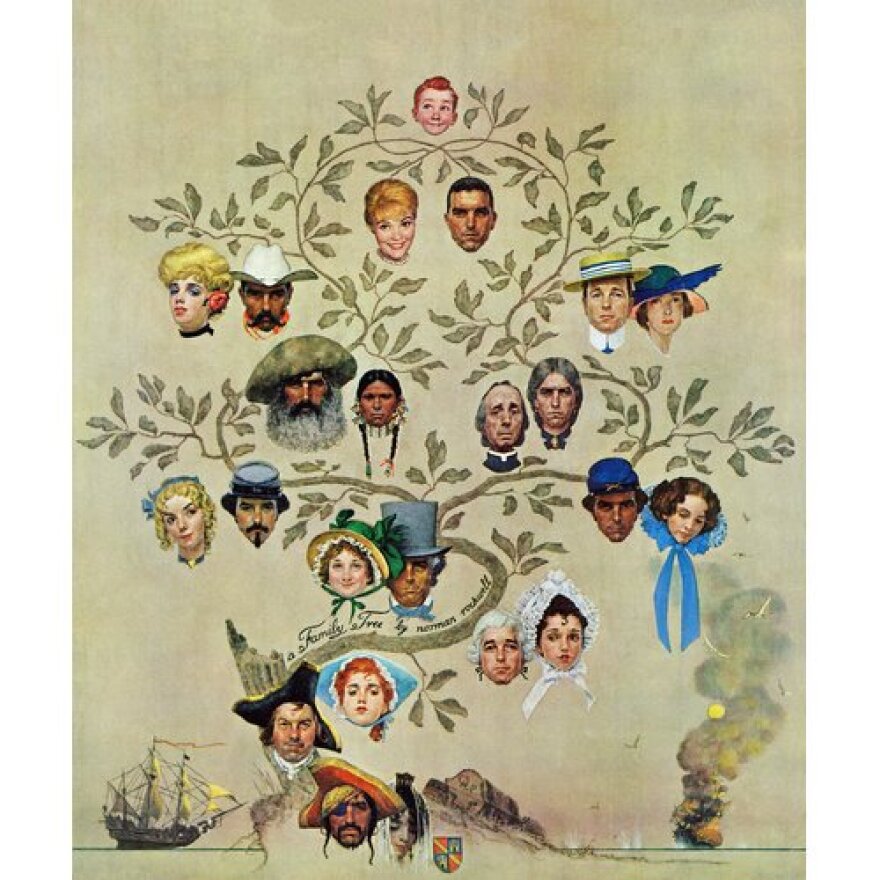

Ancestor worship was and is common in many cultures, and we still have a trace of it in our own era, especially in this age of commercial DNA testing and TV shows that promise to find your roots. Curiosity about those roots stirs only when we ourselves are older and can imagine becoming ancestors ourselves.

There was a time when family was destiny and ancestors meant everything. They still do if you happen to belong to one of the “royal” families of celebrity, politics, or money. But for most of us, what we hope from our ancestors, I suppose, is that they will not be too embarrassing and may shine the oblique light of their distinction on us, if they had any distinction. In this sense, genealogical research is a kind of self-esteem therapy.

But if the ancestors are disappointing, there are always the descendants. In fact, I get the feeling that we are seeing a cultural shift from ancestor worship to descendant worship. The intense focus on children is surely something new. Back in the days when people revered their ancestors, children were of little account and were largely ignored. Ancestral portraits hung on the walls. Now it is children who are photographed and videoed every minute, their images displayed in the house, e-mailed to relatives, posted on social media, and applied to greeting cards. It’s clear that they, not the ancestors, are at the center of the family universe. These soon-to-be-exceptional children shine the light of distinction as it were backwards, from their future success. Anything can happen in the future, so pride doesn’t have to wait. Children are the future, of course, and ancestors are the dreary black-and-white past, when nobody even had a 17G cell phone. But the ancestors had one advantage: they offered a reality check. If they had no distinction, we could forget about them and focus our attention on the present. As Voltaire said, “Do well in this life, and you will have no need of ancestors.”