Nowadays we take for granted the ability to just turn on our car radio when we want news, music, or entertainment while traveling about. Such convenience was not always the case.

Prior to the 1930s, the car radio would have been considered a novelty at best, and a rare one at that. Technological limitations, cost, and size limited car radios to the hard-core radio experimenter and, perhaps, a few high end automobile models driven by the rich and famous. Technologically, early car radios faced several hurdles. Power was a problem. Most cars used 6 volt batteries at the time, and most 1920s radio sets required several voltages to operate, typically 2 - 6 volts for the tube filaments, 90- 250 volts for the radio circuits, and negative 4- 9 volts for what was referred to as "grid bias," which was used to control the gain, or amplification, of the tubes.

Radios themselves were not small, and the only way to practically obtain these voltages was to outfit the vehicle with an additional bulky battery box to supply the radio. This added to the problem of where to fit the radio. These batteries were also expensive and short lived.

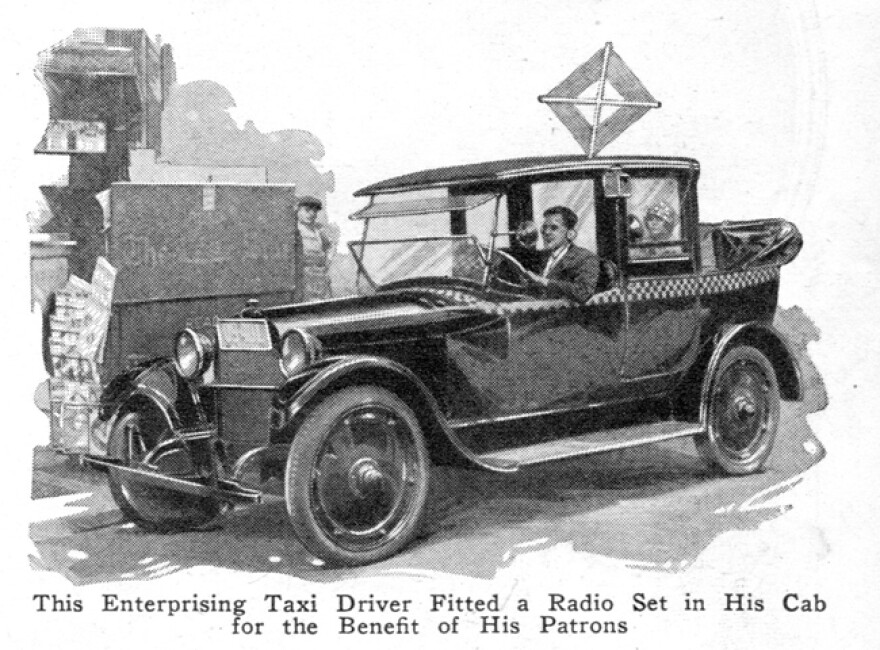

Antennas were another factor. Early radios were not all that sensitive, and at were usually hooked to long wire antennas, strung between the owner's home and a nearby tree. The majority of articles that I have found in vintage radio magazines about how to put a radio in one's car dealt with ways to create a usable antenna. These often suggested large coils of wire hidden under the chassis or under running boards, and do not appear to have been overly effective, most often described as being able to receive "local stations."

Noise was a problem. Apart from the relatively high ambient noise of the vehicle, the weak audio amplifiers and inefficient loudspeakers of the day had to compete with electrical noise from ignition systems. Ignition noise could be horrendous. The Model T, for example, featured a continuously firing "spark coil" which, when coupled to steel or copper spark plug wires, splattered noise across the broadcast band. Atwater Kent's invention of the breaker point ignition and the addition of noise suppression resistors to the spark plugs would eventually help reduce this source of interference. Other problems also plagued the early car radio. The average working man's car did not always have softest suspension and more roads than not were unpaved, and this resulted in a bumpy, if not occasionally bone-jarring, ride. Early vacuum tubes were delicate and did not take well to being constantly jostled about.

By the early 1930s things were beginning to change. New tubes were designed that allowed for the development of portable radios, and some manufacturers, Zenith in particular, pushed the idea of using their portables while in the car. The radios came with antennas equipped with suction cups that could be stuck on a car window for improved reception. This concept still had its drawbacks. The portables still required special often expensive battery packs. The radio needed to be set up and secured so it would not tumble about during sharp turns or sudden stops. It would often be held by a passenger. The stick on coil antennas were somewhat directional, resulting in signal fade when the vehicle turned from one direction to another.

In a previous essay I featured the farm radio, and looked at the technology that brought radio to rural communities prior to electrification. This technology, centered around the Mallory company's vibrator power supply, allowed a conventional radio to be powered from a single 6 or 12 volt vehicle battery. This same technology allowed engineers to design radios that could be built into a vehicle and powered directly from the vehicle’s 6 or 12 volt electrical system. Miniaturization of radio components was still about a decade away. It would be driven by the need for compact radios for aircraft and other military applications during World War II. Engineers still had to deal with how to fit the radio into the vehicle. As pictured here, the radio, often in several pieces, was located remotely, such as under a seat or in the trunk, and connected to controls on the dashboard.

In this case a hose clamp on the control unit suggests that it would be mounted on the steering column. This radio was the start of the Motorola Company. The radio was designed by Paul Galvin of the Galvin Manufacturing Corporation. He named it Motorola combining Motor plus “ola” which he borrowed from the popular record player Victrola, believing that it would make people think of music.

Fitting the radio in the car was not the only problem that the driver/radio enthusiast faced though. Today, laws are being enacted to deal with cell phone use, texting, and other distractions. Back in the early 1930s, Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, Illinois and Ohio made it a fineable offense to operate a radio in a motor vehicle. In 1935, Connecticut legislators introduced a bill that would have made the installation of radio into a car subject to a $50 fine, but were not successful in passing it. The Radio Manufacturers Association, who by now had reasonable clout on the lobbying front, fought back, and, eventually, car radios were accepted.

By the late 1930s components had become small enough that radios could be designed as a single (but still large by today’s standards) unit that would fit in a car’s dashboard. The heterodyne receiver circuit was sensitive enough that a small vertical whip antenna would suffice for good reception, ending the quest for a workable car antenna. Miniaturization brought on by aircraft needs during World War Two resulted in post-war car radios that very much resemble modern car radios. Vacuum tubes held sway in the car radio until the early 1960s, when they were replaced by transistors. FM car radios would not become popular until the 1970s.

For radio enthusiasts during the 1960s, the AM car radio reached its peak in terms of sensitivity, selectivity, and noise rejection. Until the advent of modern high end receivers with digital signal processing, the analog car radio was hard to beat for DX (the hobby of trying to receive distant stations). When hooked to an outdoor long wire antenna, and powered from a 12 volt power supply, such a car radio could easily pull in stations from across the county at night, making them a favorite for DX on a budget.