Subjective tests, private study groups, and favored treatment are a few of the systematic ways Black cops struggled to get hired and get promoted in the Suffolk County Police Department.

In 1981, Richard Wright was at the end of a long conference table being interviewed for a spot in Suffolk County’s police academy. Police brass lined both sides of the table.

“They asked me, so how did you afford the suit that you had on?” Wright said. Other Black officers already on the force had warned him it would be difficult.

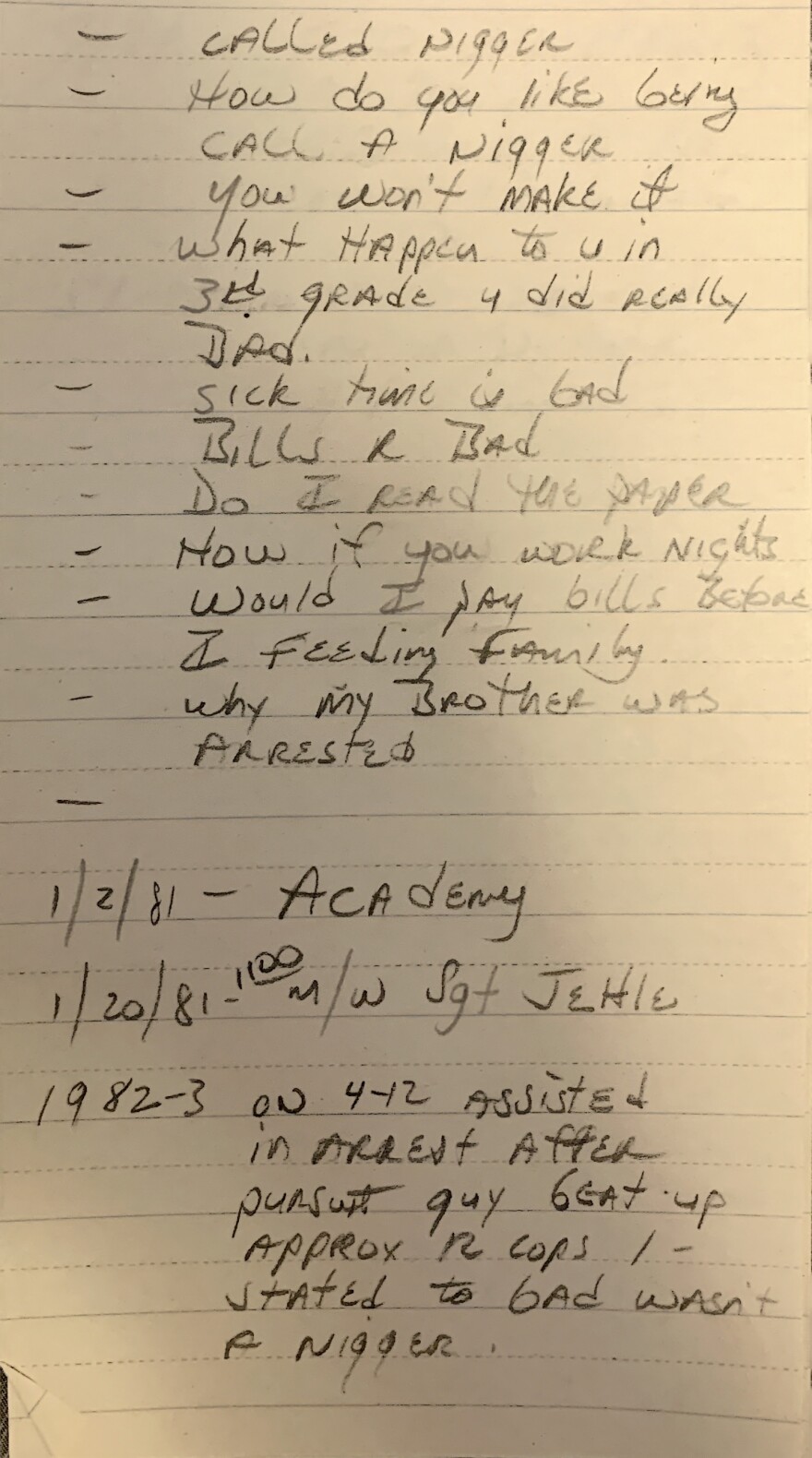

“On at least two occasions, I was called [racial slur].”

He said the insult was meant to rattle him.

“This thing went on for at least three hours,” he said. “Questions about my bills, about my background, about my family background, whether it be my in-laws, my finances, on and on.”

When it ended, Wright was so shaken he couldn’t find the door. He walked out of police headquarters and got in his car.

“Just sitting there and crying. Because I held myself as long as I could,” Wright said. “I never had gone through something like that. I always felt that I was the one that was chosen that they were going to fail.”

Wright served 28 years on the force, retiring in 2009. He’s a member of the Suffolk County Guardians, a fraternal organization of Black police officers. Up until the pandemic, he still attended meetings.

“From what I hear from other officers, no, it's not better,” he said. “Yes, they do have their difficulties with movement in the department.”

Wright was among eight current and retired officers who describe a department where not being white meant it was harder to get hired and promoted. That ultimately led to unequal policing, they said.

'You probably will never get another assignment, if you were to openly speak out against the department,' Richard Wright said.

Only retired officers agreed to have their names published. They include: Kenny Williams, Howard Keith Belfield, Calvin Powell, and Richard Wright. Four others, both on the force and retired, feared retribution and only agreed to be interviewed provided they remained anonymous.

The police department refused to allow current members of the force to be interviewed for this story.

Same Numbers After 40 Years

When Wright was first hired, there were roughly 60 Black police officers on the force. Forty years later, there are 64.

The department is overwhelmingly white: 85%. And while Suffolk has made strides in increasing the number of non-white police officers, they are mostly those who self-report as Hispanic.

About 8% of residents in Suffolk’s police district are Black. Less than 3% of the department is Black. To reflect the community it policies, Suffolk would need to hire 130 more Black officers — three times what it has now.

“The numbers speak for themselves,” said Calvin Powell, who supervised one of the largest increases of minority police officers in the department’s history — an effort called the Community Service Aide program. “The purpose of this program was to increase the number of minorities in the police department.”

Powell retired in 2010 and is a former president of the Suffolk Guardians.

He said Community Service Aides were allowed to test for the police academy. But he said many Black applicants were — to use Wright’s words — “chosen to fail”.

Powell said the department tried to do this to him.

“I was given a written psychological examination with a bunch of vague and arbitrary questions,” he said. “My results were that I failed a psychological exam.”

He appealed and hired a private psychologist. He was admitted to the force and went on to serve 30 years, eventually rising to become a hostage negotiator.

“Many other African American police that I've talked to over the course of my career experienced the same exact situation,” he said. “In my opinion, it's nothing more than an effort to discourage, then at that time, African Americans from joining the police department.”

Where Black Applicants Fall Off

“I know exactly where the numbers fall off,” said Kenny Williams, a former president of the Suffolk Guardians who retired in 2007.

Williams was in charge of officer recruitment. He said the department mostly succeeded in getting Black applicants to take the entrance test. It’s after that, during the background checks and the psychological test where Black applicants fail — like Powell.

“There is a lot of subjectivity in those qualifying tests,” Williams said, “and all the standards were not equally applied or cases were handled differently.”

Suffolk Police officials did not respond to multiple requests to provide demographic statistics on the applicants screened from the academy.

Data was revealed in a civil rights lawsuit where a Black applicant in 2014 passed the entrance test but said he was unfairly dismissed because of a psychological test — the same as Powell.

The data submitted as part of that lawsuit shows that 90% of cadets were white and 4.5% were Black, below the police districts population. The county settled the discrimination lawsuit for an undisclosed amount.

Suffolk has been routinely criticized for the paucity of Black officers since at least 1986 when it entered into a consent decree with the U.S. Justice Department over this very issue.

Police officials declined multiple requests for an interview. However, as part of a state-mandated reform process, they publish statistics indicating that 5% of those invited to advance to the academy identified as Black or African American. This percentage is disproportionate to the police’s jurisdiction, but doubles what it has now.

During public meetings regarding police reform, officials repeatedly assured skeptics that the department would change.

“One woman spoke about how rich, white people are going to make the decisions. That’s not true in this one,” said Risco Mention-Lewis, an African American deputy police commissioner. “I’m at the table. I’m doing the research.”

The county’s police reform task force is expected to issue a draft report in the coming days. Its contents are unknown, but one of the task force’s subcommittees is focused on hiring in the department.

Private Study Groups

Getting hired is one challenge for Black cops. Getting promoted is another. Promotions to sergeant and above are determined by scores on civil service tests.

“It always seemed to us back then that the boss's kids were always really super smart, because they all seem to do really well on the test,” said Howard Keith Belfield, a former president of the Suffolk Guardians who retired in 2007 as a detective.

Belfield said some officers had the benefit of private study groups for these tests.

“In order to get into these private study groups, you had to know somebody,” he said. Belfield said what makes these study groups so helpful is that they have collected a bank of questions to the civil service test.

“There’s some guys that were pretty good test takers. They went around and took other tests throughout the state,” he continued.

Belfield and others said a group of them memorized the questions and then organized private classes.

“But it was only certain people who got into the classes,” he said.

Both current and former officers interviewed by WSHU confirm the continued existence of these stored banks of answers to the civil service tests. Sharing such material is a misdemeanor.

They said Black officers are not purposely excluded from these groups. Rather getting access to this question bank requires what some cops called “a hook.” Others used the phrase “someone who can make the phone ring”.

Can You Make The Phone Ring?

Belfield's preferred term is the "rabbi system"*. It's an anti-semitic and derogatory trope in common parlance among police officers. It refers to the help that some cops receive in getting promotions through favoritism or nepotism.

“Guys had 'rabbis', you know, the chief who liked you or someone that you're related to or a neighbor of,” Belfield said. *

He said this system is self-perpetuating. When all the high ranking officers go to the same barbecues or go to the same church, they promote people who look like them.

Belfield said this is how James Burke, the former chief of police, got away with years of indiscretion. Burke served three years in prison for beating a handcuffed man and covering it up.

“How did he make it from PO to chief of department without having some type of 'rabbi' or a hook?” he asked. “That's the 'rabbi system' right there, that's the hook. That's the big hook.” *

During meetings of the Guardians, members would talk about all the ways white officers would get out of trouble.

“We'd be fired for that and these guys can get away with it,” Belfield said.

As recently as 2019, evidence of this favoritism went public when Detective Sergeant Jeffery Walker, vice president of the Suffolk Guardians, went before the county legislature to complain that he was passed over for a promotion.

“I went for an interview and I was told that, ‘You know the way it is, Jeff, you know, politics, you’re not getting the job,’” he told lawmakers.

The promotion Walker sought was offered to the nephew of the chief of detectives. Following inquiries from the Department of Justice and after the legislature hired a special prosecutor, the promotion was rescinded.

Police Commissioner Geraldine Hart declined several requests for an interview. For over a week, a department spokesperson said WSHU’s questions and requests for information “were being worked on.”

Ultimately, the questions were never answered.

In 2019, Hart told the legislature that promotions are never political.

“The police department has made a concerted effort to change the way promotions are awarded to ensure that a merit based system is in place,” she said.

Hart said the department has significantly boosted opportunities to minority officers.

“We have seen a steady increase of minority transfers into specialized commands with the highest number in 2018. And we are on pace to break that in 2019,“ she said.

Data shows police brass is overwhelmingly white. There are 395 white officers above the rank of detective. There are 30 that are non-white; Of those, four are Black.

“I hear good things about this police commissioner,” Belfield said about potential changes that Hart could make to make the department more equitable. “She could want to make it happen, but if the county executive and the legislators don't want it to happen, it ain't gonna happen.”

* The story includes an antisemitic use of term "rabbi" when current and former police officers describe a person that helps others get promoted through favoritism ahead of Black cops.

The analyzing of derogatory and racist terms used by police is part of state-mandated reforms.