Dr. Dan Tobin of Yale-New Haven Hospital was just a resident -- kind of like an apprentice physician -- and it was around the year 2000 when he ran into a problem he’d never seen before.

“One day I got a phone call from a local pharmacy that said, ‘Hey Dr. Tobin, did you prescribe ‘mofine?’” he said. “It turned out somebody had stolen a prescription pad and tried to put my name on it.”

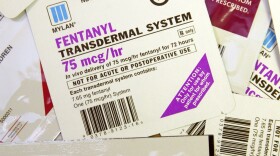

That was his wake-up call. Doctors who prescribe painkillers have a big responsibility: they may have to decide if a patient is at risk of opioid abuse.

“Frankly, I was sort of naive to some of the misuse that occurs, until I experienced that,” Tobin said. “Really opened my eyes that it’s not so straightforward anymore.”

Tobin’s a primary care doctor now. He’s watched as deaths from opioid abuse have more than tripled since he was a resident. About one in four people who abuse opioids get them directly from their doctor. Sometimes people lie to their doctor to get pills. Then there are the cases Tobin says are the hardest to face. That’s when people really are in pain, but get addicted to the relief the pills give them.

“When we become physicians, one of the most important things that we care about is ‘do no harm,’” he says. “I can’t cure everybody, but I could always try to help people feel better. And the thought they may go on to develop a problem because of something I did really just tears you up inside.”

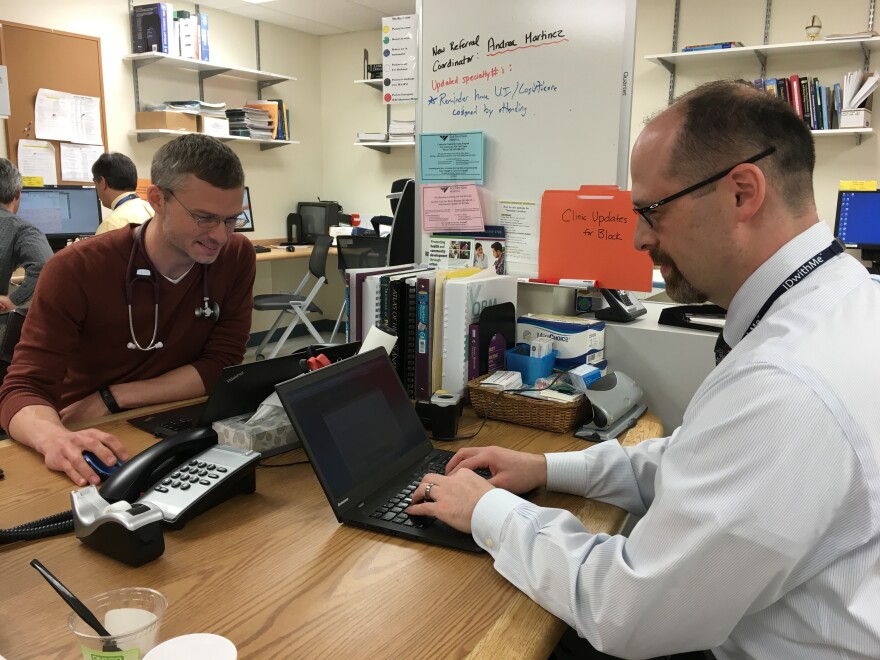

When a doctor at Tobin’s primary care clinic isn’t sure if they should give a patient opioids, they come to a room he calls the command center. Doctors and residents work away on computers or chat around tables. Tobin usually talks to his fellow doctor Steve Holt, who treats addiction, first. But not every primary care clinic has an addiction specialist like Steve Holt on hand. Holt says a lot of doctors operate in the dark.

“Talking about addiction is taboo,” he says. “Either they don’t believe their patients are going to be susceptible to addiction, or they don’t want to accuse patients of being at risk.”

Tobin says that’s because of a lack of education. Doctors who specialize in pain management learn how to tell if people are at risk of opioid addiction. But there aren’t that many pain specialists in the U.S., compared to doctors like Tobin, who treat everything.

“My patients, they don’t have a lot of resources to go to pain specialists,” he says. “So that means the primary care doctor, like me, we’re the ones who do all the prescribing.”

Tobin says that’s why it’s important for primary care doctors to know what they’re doing. He gives training to doctors around the country, and tells them it’s tough to make the call if a patient needs opioids. But it’s their duty as medical professionals to make the best call they can.

“I hope that primary care doctors aren’t so discouraged because they’re worried and nervous, either at causing harm or being investigated, that they’re gonna just bow out,” he says. “I think that’s really not going to help anybody.”

Tobin says it’ll take a lot of different approaches to make a difference in the country's opioid epidemic. But he says there’s no more qualified group of people than the ones on the front line of preventing opioid abuse.

“Primary care doctors, this is what we’re good at,” he says. “We take multiple complex chronic illnesses and we have to manage them safely. This is no different.”

Last week, Connecticut Governor Dannel Malloy signed a bill into law that’s supposed to cut down on opioid abuse that starts in the doctor’s office. It limits many opioid prescriptions to seven days and sets up a task force to look at better ways to catch opioid misuse before it turns deadly. And Tobin will be a part of that group.