"An explosive situation is brewing in New Haven over the impending Black Panther murder trial and the times call for an immediate lowering of the heat and cooling off of passions."

This was the opening line to an editorial that appeared in the New Haven Register on April 23, 1970.

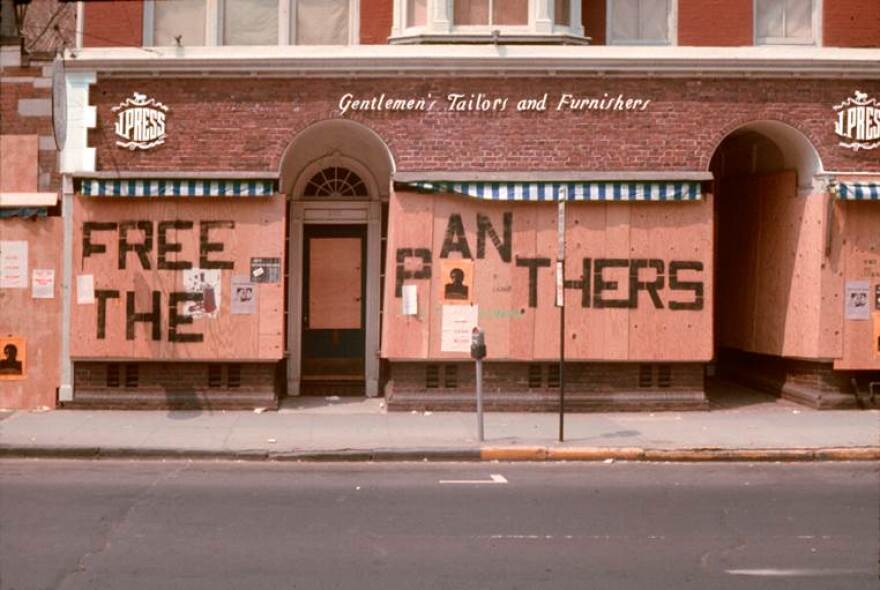

New Haven was preparing for a May Day demonstration supporting the Black Panthers and decrying the official authorities of the city.

Fears grew that the violence which had erupted in other cities would come to New Haven.

At the time, Henry "Sam" Chauncey was an assistant to the President of Yale University. He was assigned the task of dealing with radicalism on and off campus.

Chauncey has co-authored a book that documents the days leading up to the May Day Protest in words, images, posters, and news clips. It’s called May Day at Yale, 1970: Recollections: The Trial of Bobby Seale and the Black Panthers.

Interview Excerpts:

You had 6 weeks to come up with a security strategy for the campus. What was the first thing you did after getting that task?

The first thing we did was to see what other universities had done who had already had radical upheavals of some kind. We learned immediately that no one had been successful by just throwing policemen at the students. The second thing we did was to consult people at other universities, and I mentioned particularly a man named Archibald Cox, who had the same job at Harvard that I had at Yale, and Harvard had not been successful. And so we talked to him and he said...

Tom Kuser: And this is the same Archibald Cox that...

Henry Chauncey: ...who became Solicitor General of the United States. He said you have to find a way to embrace the radicals; if you throw police at them it won't work.

You say in the book that the majority of those radicals who would be involved in the protests weren't dangerous and had legitimate agendas for social change. It almost seems like a contradiction in terms, a non-dangerous radical. Was this an unusual perspective then?

I think you have to think a little bit about what the word "radical" means. I take that word to mean someone who holds an opinion that isn't particularly popular today. They're not necessarily dangerous opinions. There were very dangerous radicals. The worst of the lot were called the Weathermen. People who study this period know that they did kill people, bomb buildings, and so on. But there were many, many young people, and older people, Martin Luther King was in my opinion a radical, because he held an opinion about voting rights for minorities which was not popular at the time. He was a very successful radical, and he was a moderate radical because he didn't believe in violence. So it's how you look at radicalism, and that's one of the things I learned from my experience during May Day was you don't judge people just because their ideas are different from yours as being bad.

There was a danger to the Yale campus from the Left but you say in the book, too, there was a threat of danger from the Right as well as from the Left. Who from the Right?

It started with the President of the United States. We learned later, through Freedom of Information inquires that we made, that President Nixon wanted very much to have an explosion on what he referred to as an elite campus. And the reason for that was that he thought such an explosion would move people who were in the center of the political spectrum to the Right. He and his aides, we subsequently learned, had talked about that. Thus, the head of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, was ordered to sort of keep an eye on things. We know Mr. Hoover ordered our phones to be tapped. And they were looking for opportunities, I think, to almost encourage an explosion. So we had the prospect of the Weathermen on the Left possibly and the people from the right wing on the Right, which made it quite scary.

When you say explosion, do you mean a literal explosion, or an explosion of people protesting?

I think politicians in Washington wanted something that was of sufficient news value to cover the country. And that would mean probably something more than just a protest. But the possibility of people being killed, the possibility of buildings being burned down, the possibility of a university president being fired, something to capture the imagination of the broad country. So I think the word explosion is meant in sort of its maximum terms.

In attempting to keep the peace on the Yale campus you said the ends justified the means. Did you mean that some of things that you did, or thought you would have to do, were unethical?

Yes. We wanted to accomplish three things. We did not want death and destruction. We hoped very much to keep the ongoing academic activity of the university going, and we also very eager to separate the moderate radicals from the hard-nosed radicals. In doing that, we did things such as arranging the hijacking of the Weathermen's bus, the Weathermen who were coming from Boston. Now, I don't know whether it's illegal to hijack a bus or not, I expect it probably is, and it may even be unethical. But our feeling was that preventing people from being killed, and, parenthetically, one wants to remember that six days later four young students were shot at Kent State by the National Guard. But people had died in these events and our goal was to not let that happen. So I think we did things that today someone might question if they were ethical. I guess I'm prepared to live with that.

And we should point out the hijacking of the Weathermen's buses was not a violent hijacking, it was a mechanical one.

It was a mechanical hijacking, that's right.