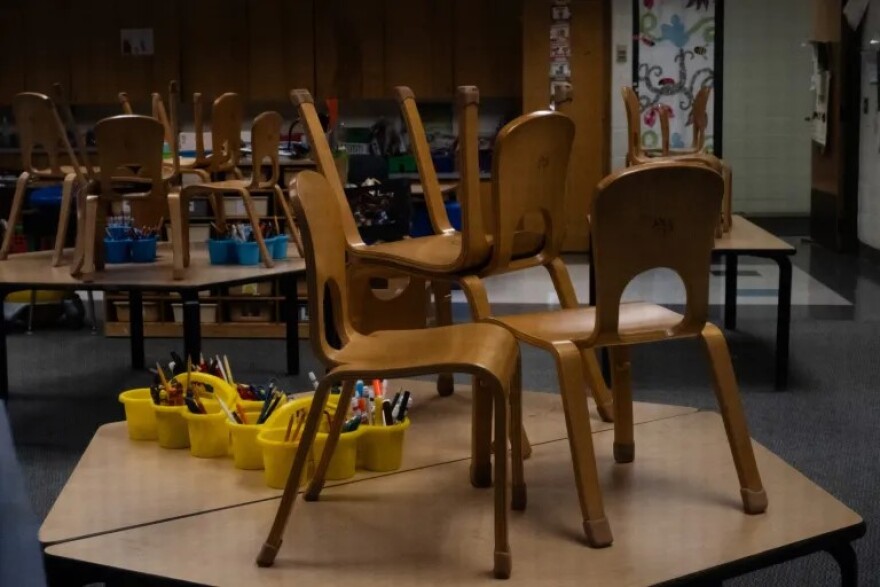

As school districts across Connecticut work to balance their budgets while facing declining enrollment and possible fiscal cliffs when pandemic relief funds run out in September, some are now making decisions to consolidate schools to help save costs later.

In the last decade, Connecticut has closed more than 75 public schools, most of which taught primary school aged children, according to data from the state Department of Education. In the same time frame, the state has also lost more than 36,000 students, from an enrollment of around 550,000 down to 513,000. Enrollment levels in the last three years have generally flatlined.

In 2023 alone, five Connecticut schools shut down, including two in Mansfield when three elementary schools were consolidated into one. Mansfield Superintendent Peter Dart said the district had experienced “a slight decrease in enrollment,” but the consolidation effort was “more about the replacement of sub-standard, inefficient buildings with small enrollments.”

Mansfield is not alone.

Dart said he anticipates other districts will follow suit after discussions with fellow superintendents.

“It is definitely an ongoing conversation,” Dart said. “I think all superintendents understand that paying attention to enrollment and enrollment projections is absolutely imperative. At the same time, the culture and climate of a community is always realized in how people love their neighborhood school. I know superintendents are cautious. They’re hesitant to simply just move an idea forward knowing that change is hard for families.”

At least one district in the state — Regional School District 13 — has found itself in a tug-of-war between its board of education and parents over consolidation efforts as the district worries about finances. Parents have pushed back against school closures for several years.

“It’s tough, especially with regional districts,” said Lindsay Dahlheimer, the district’s Board of Education chair. “A lot of [people] don’t take into account declining enrollment … and [how it’s] detrimental for us to be able to navigate a district effectively.”

The regional system, which educates students in Middlefield and Durham, has three elementary schools for about 650 K-5 students — down from 830 about five years ago. Local school officials say that many buildings doesn’t make sense, especially when the three public schools educate different age ranges — pre-K to 2 at one campus, K-4 at another and a third school serving grades 3 through 5.

For months, the Board of Education has considered the construction of a new school, which would house all K-5 students, or the closure of one of the campuses — two options they say would save money in the long run.

Parents, however, have been reluctant to consider any school closures, which has left the district struggling to maintain its current buildings. It has resulted in an interim plan where its elementary school children will transition between each of the three schools every few years in order to make use of existing space and align academic tracks for all students.

In this scenario, all pre-K through first grade students would attend one school before transitioning to a new school building for second and third grades and then attend another school through fifth grade before the move to the middle school.

The decision, expected to go in effect in the fall, would ultimately eliminate the district’s school choice model and leaves uncertainty on how long the temporary solution may be in place.

“Unfortunately, we have to do what we have to do with what we have and what we’re able to utilize,” Dahlheimer said.

The decision has contributed to growing friction among some families and the district, as parents not only have been in vocal opposition of the board’s decisions but also argue that the interim plan will be detrimental to student learning, self-confidence and student relationships.

“Educational research has shown that more transitions lead to negative outcomes — academically, behaviorally, socially, emotionally — for these young learners,” said Jennifer Simmons, a parent in the district who also works as a counselor. “When you combine the stress of new transitions with the rapid developmental growth at that time, it’s just too much for their little system.”

But some experts argue transitions don’t have to be bad, if paired with the proper support services.

Though a unique situation in Durham and Middlefield, considering it’s unusual for students to move to a new campus at least two times before fifth grade, it has the potential to play out across dozens of other districts. There are at least 81 schools that require some kind of transition before the fifth grade, and statewide enrollment levels may trigger more closures or consolidation efforts in years to come.

A larger issue

Regional School District 13 is in line with other districts across the state and country that have been struggling with having too many buildings to maintain and not enough students to offset the costs.

Connecticut’s trends are similar to the rest of the country, as data shows that nationally 12% of public elementary schools and 9% of middle schools had enrollment declines upward of 20% during the early pandemic years, according to Brookings, a nonprofit organization that researches public policy issues.

Data from the federal Department of Education shows that more than 700 public schools shut down in 2021-22.

Resistance to these closures is not unusual and has been playing out across the country in cities like San Antonio, Salt Lake City and Rochester, New York.

In Mansfield, the years of consideration and parental opposition to consolidation was similar to what’s now happening in Regional School District 13 and other districts across the country.

“We still hear [resistance] and feel it. People love their small neighborhood school. … [But] I think that the transition into the new building has been exciting. We’ve had a community that has embraced our changes, but not without the struggle and the transition of realizing that our three neighborhood schools have closed,” Dart said. “[Now,] we have an opportunity to brand a new school with new programs while embracing some of those old practices.”

Dart’s district has already seen “an immediate savings of more than $1 million” since the new elementary school opened in April, he said, adding that it’s allowed greater room for innovation and expansion of academic programs.

“The sweet spot really is trying to find ways to be efficient — to recognize when consolidation is appropriate — but also to allow students, staff and families see themselves through that process and change,” Dart said.

In the last 10 years, most Connecticut school closures have occurred in areas that educate large populations of students of color, including Hartford and New Haven. Research has shown that school closures often disproportionally impact Black and Latino students.

Region 13

In a 2021 referendum, Middlefield and Durham residents voted down a proposal to shut down its K-4 school, John Lyman Elementary.

Lyman, now up again for closure, housed the Integrated Day program, which Dahlheimer described as an “arts and music integration school.” However, since 2018, the district began its consideration of combining elements of the arts program with more traditional methods of instruction typically seen at most elementary schools.

Dahlheimer said she believes parents may be struggling to separate the school building from their love of the program, which contributes to the pushback against the closure.

“I think you can see a very big divide, and the divide has been there for a long time, and it’s not necessarily by town. It’s the Integrated Day program, the separation of the [schools] over the course of history and not wanting to let go of something that truly was an amazing experience for your children and trying to separate the program from the building,” Dahlheimer said. “I know it is hard. It’s hard for families that have kids that are younger and older siblings were able to go through the program — so they see it as a big loss, and I sympathize with it.”

The district’s current plan to realign its elementary transitions means students will attend Brewster Elementary School from pre-K through first grade, Lyman from second through third and then Memorial Elementary School for fourth and fifth grade.

“[We wanted to take] these five schools [including middle and high school] and bring all these kids together along grade level, for these kids to know each other from the moment they start their education,” Dahlheimer said. “I’m hoping it will improve retention because these kids have relationships from the beginning of school all the way through, so they’re less likely to want to leave when they’ve been with their peers since the beginning, as opposed to say fifth grade when they’ve been coming together.”

Responses to the interim plan from families in the district, however, have been split.

Some families say the situation isn’t ideal but that it makes sense for the future.

“The end result is having one school where our kids can hold hands and walk in together, where we can have preschoolers and kindergarteners looking up to fifth graders, where we can have all-school assemblies,” said Janina Eddinger, who has six children attending schools in the district, at the September board meeting. “If we chose that option, and let the board move forward, then we can have that rosy world. … It’s going to be a hard transition in this interim, [but we need to] trust our kids are really resilient, even though we think they’re not half the time.”

Others argue the transition model is “unethical” and that the decision was rushed. Mary Ann Wellborne, a parent from Middlefield, expressed concern at the September board meeting about research showing the “damage that happens to kids” who go through multiple transitions.

“The collateral damage with math, literacy [and] emotional, psychological development — it doesn’t feel acceptable to the children in our community,” she said.

An online petition opposing the plan, with more than 30 signatures from educators and psychologists, was presented to the board in fall 2023, but even some experts say the impact of early transitions can be a spectrum depending on support services.

“Prior studies show that poor transition experiences can negatively affect a child’s academic achievement, social-emotional competence, and behavior,” the federal Department of Education said in a blog post. “Efforts to support children’s positive transitions, however, can strengthen early success.”

Stephanie Tavarez, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Hartford, said transitions may be beneficial if they’re done correctly.

“I think transitions are good, but what environment is the child around to support these transitions? That is my biggest thing. If the school wants to make the shift, they have to make sure to provide that support — academic, social, emotional, especially emotional. Is there any emotional intelligence support for kids to actually be able to adapt with the anxiety that they deal with or the stress that they feel moving from school to school? Are we giving them the resources to really handle that right?” said Tavarez.

Dahlheimer said they’ve worked to engage parents through meetings with local PTOs and board members. As for the actual students, the district has been considering different support measures, including opening buildings earlier so students can get to know their new surroundings and teachers to help ease the move between campuses.

In Mansfield, there was also a concern about transitional impact on students, given the district moved its elementary school children into a new campus mid-spring semester. It went better than expected, though, Dart said.

“They adapted very, very quickly, and they loved the fact that they were able to see friends that they knew from their little league teams and scouting groups. They loved the fact that they were all in one place,” Dart said. “I think it’s sometimes the adults that struggle the most with the uncertainty in different routines.”