Scientists from the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station are helping the indigenous Miꞌkmaq people in Maine cleanup toxic PFAS chemicals on tribal land near a former U.S. Air Force base.

They are using hemp plants to decontaminate 600 polluted acres of land the tribe reclaimed in 2009, when the U.S. government turned over the former Loring Air Force Base. These chemicals are common in lubricants in defense manufacturing and in firefighting foam that were banned for use at airports across the country.

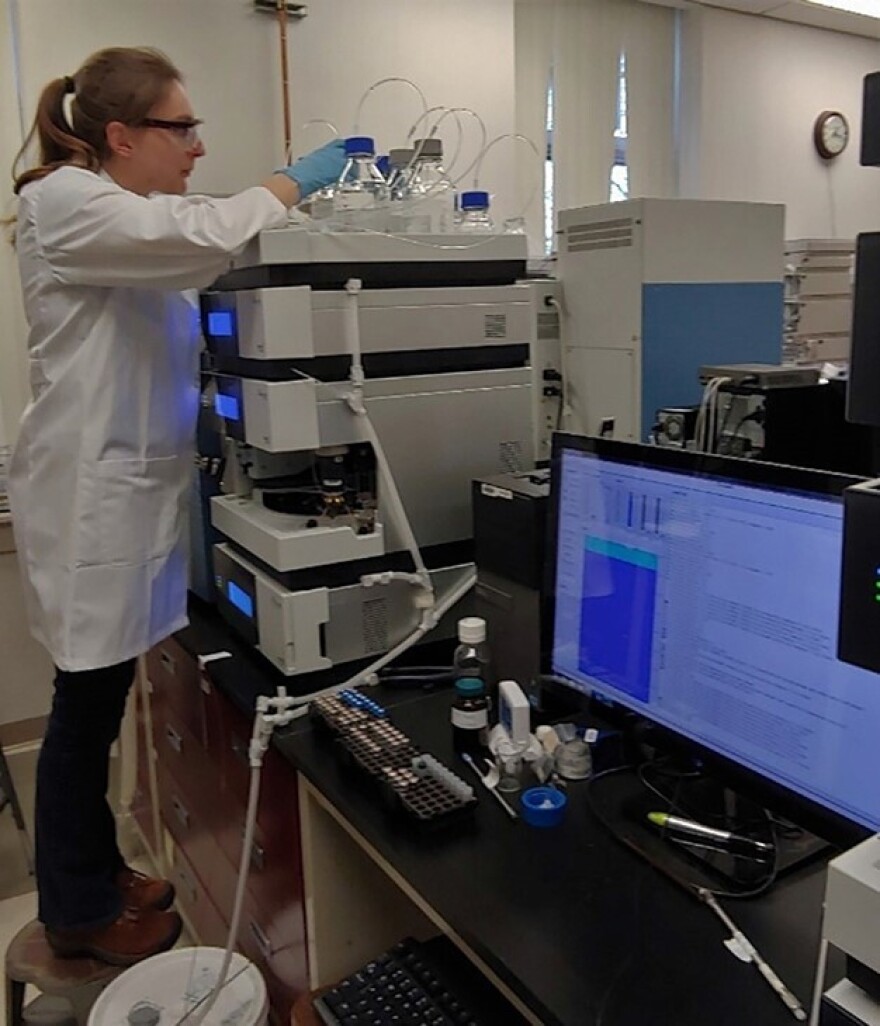

Sara Nason, a biochemist at the experiment station, said the process is called phytoremediation.

“The plants, as they grow, will either produce chemicals and bacteria in their roots that will help to degrade the chemicals over time, or that the chemicals will get taken up into plants with all the nutrients and water the plants take up. And then if you harvest the plants, you’re removing the contaminants from the site,” she said.

Nason said hemp grows fast and consumes a lot of the contaminated groundwater. She said the plants have had a positive effect in reducing the amount of PFAS at the test site so far.

Further research is needed to determine if the contaminated hemp plants can still be used safely for other industrial purposes or whether they will have to be destroyed because of the PFAS they contain.

“What we want to do in the future is to take larger plants to then separate out the different plants and the buds and the seeds and the stem fibers and then measure to see where the contaminants end up specifically in the plant, and which parts might be able to be used safely,” Nason said.